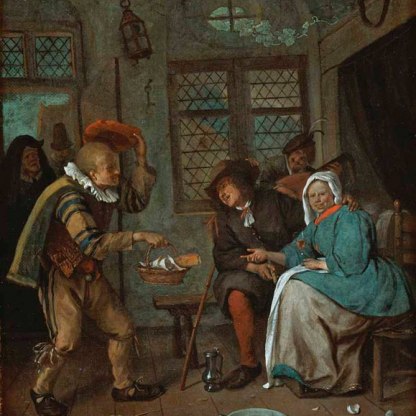

A Village Festival in Honour of St Hubert and St Anthony

Despite the title, it is not immediately obvious that the festivities being enjoyed in this painting have anything to do with religion.

The viewer looks down upon this busy village scene from a distance. In the foreground children brawl over a few coins. One man leans on a barrel with his face in his hands – the epitome of drunken dejection – while another encourages a young boy to swig from a jug the size of his head. Pigs sniff around a huge cauldron, while a few feet away a couple embrace.

At the far right, a man vomits extravagantly onto the ground among the chickens. Nearby, people dance and play bagpipes. In the distance a man empties his bladder against a wall.

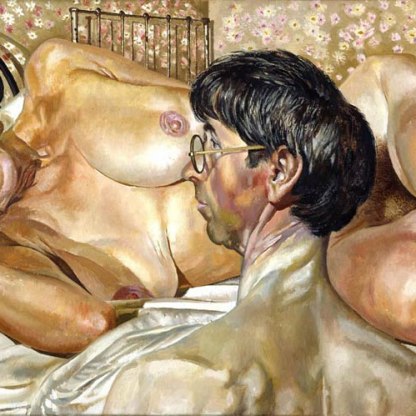

In the centre of the picture a large crowd has gathered around a stage to watch a play in which a man dressed as a monk kisses a buxom woman, while another man spies upon them from a basket on a colleague's back.

On the right of the painting, we eventually see the excuse for this communal exuberance. Ignored by the majority of villagers, the statues of two saints are processed towards the village church. Preceded by a banner and holding the hunting horn by which he was traditionally identified, is St Hubert, the patron saint of hunters. He is followed by an image of St Antony, the desert-dwelling hermit saint whose renowned asceticism was the very opposite of the revelry going on in the village.

Members of the crossbowmen's guild, their weapons slung over their shoulders, lead the procession towards the church, perhaps for a service of thanksgiving before a hunt.

So many of the details in Brueghel's painting fascinate and entertain: the travelling players' makeshift platform and the glimpses we get of the activity backstage; the proximity of tavern and church in the background, a matter of grave concern to Dutch moralists in the seventeenth century.

Then there are the people themselves – the cripple begging near the very centre of the canvas; the man trying to climb into the cart that is already too full of travellers; four children chasing a motley-clad jester.

The whole is a fascinating panorama of contemporary northern European village life. But the scene is generic rather than specific, and Pieter Brueghel II was working in a tradition of village festival illustrations that was popularised by his father in the sixteenth century.

What are we to think of these flirting, drinking, puking villagers? Is this an abuse of a religious festival that the artist regrets or condemns? Or are the peasants being celebrated for their straightforward, earthy humanity?

Certainly, since the sixteenth century, there had been those who lamented the reputation the Dutch had for excessive drunkeness. One William Brereton commented of a village festival he attended near Dordrecht, in 1634:

I do not believe scarce a sober man was to be found amongst them. Nor was it safe for a sober man to trust himself amongst them, they did so shout and sing, roar, skip and leap.

But there was another view of such behaviour, a view that drew no strict moral judgements. A print from 1623 showing drunken peasants in close proximity to gentlefolk, begs indulgence for the village-dwellers, who have toiled all year in the fields. One can just as easily react to their antics with a smile as a frown. As was said of the peasant paintings by Pieter Brueghel II's father

There are few works by his hand which the observer can contemplate solemnly or with a straight face. However stiff, morose or surly he may be, he cannot help chuckling or at any rate smiling.

Central to this painting is the theatrical performance in the middle, and an analogy can perhaps be drawn between this type of farce and this kind of painting. Plays like that being performed here managed to marry earthy language and bawdy humour – jokes about adultery, lecherous priests, drinking games – with basic Christian truths. As the conclusion to this play says:

Now go and may Mary protect you all,

And her son, Jesus of Nazareth,

And may he grant you all peace and happiness.

Conduct your marriage in such a way

That you may enjoy life everlasting.

The moral may be perfunctory but there is nothing to say that it is not sincere. As in the play, so in the painting: the overall effect is comic, perhaps satirical, but not excessively condemnatory.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

Christie's 27 April 1917, anon. sale, (94) bought by Lord Rothermere through Brown and Phillips, The Leicester Galleries

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Given

- Dates: 1927

Dating

- 1630s

- Production date: AD 1632

Maker(s)

- Brueghel, Pieter, the younger Painter

Materials used in production

Read more about this recordStories, Contexts and Themes

Other highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…