Two Young Men

According to Karel van Mander, an early biographer, Crispin van den Broek was

a good inventor ... clever at large nudes and just as good an architect.

But even van Mander had difficulty saying much more: 'I do not know any more particulars about him because my request to those who knew them was not granted.' The two anonymous young men in this panel keep their secrets similarly close to their chests.

At first glance it seems to be a straightforward double portrait of two prosperous-looking, cheerful young men. They wear smart clothes, Italian in style but which could easily have been worn by men of fashion in the sixteenth-century Netherlands. Their relationship is clearly a close one: they touch each other gently and unselfconsciously on the shoulder and forearm. One gazes and smiles at the other. In the centre their forefingers brush lightly but deliberately and the boy in black seems to be offering his friend an apple. At the same time he stares out and smiles at the viewer. His direct and friendly gaze involves us in the painting and yet we are separated from the pair, viewed as they are through a stone arch.

At the top left and right are the heads and wings of two putti, peeping over the edges of the arch at the young men. But more sinisterly and unexpectedly, within the white, cloudy background, a crow’s or raven’s head juts out from behind the head of the boy in red, while two dark, scarcely focused owl's faces peer over each shoulder of the boy in black.

In its motif of one figure offering another an apple, van den Broeck’s picture resembles representations of Adam and Eve. The apple from the Tree of Knowledge, which the serpent persuades Eve to eat, and which she then gives to Adam, was from an early time associated with sexual pleasure. Some northern European depictions from this period explicitly show a naked Adam and Eve embracing while she hands him the fruit.

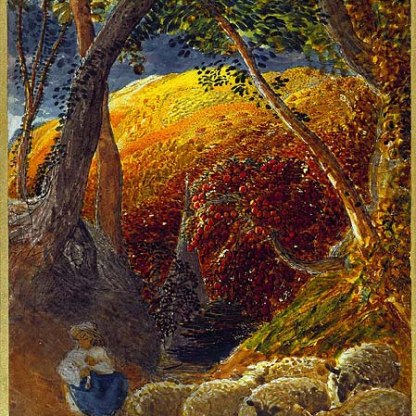

In classical art and myth the apple was closely associated with Aphrodite, the goddess of love. She was awarded a golden apple by Paris, who judged her the most beautiful of the goddesses. This event, which caused the Trojan War, is shown in an early seventeenth-century painting by Hendrik van Balen in the Fitzwilliam, left [416].

So, given the well-established erotic connotations of the apple, and taking into account the two boy's obvious mutual affection and physical intimacy, it might be tempting for the modern viewer to conclude that they are homosexual lovers. This is however unlikely. In northern Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the civil and religious authorites were uncompromising in their condemnation of homosexuality. With their distinctive reddish hair and similarly shaped faces, the two young men are more likely to be brothers.

Death rather than sex is more clearly alluded to. The stone panel in the top centre of the picture, bearing the artist's initials, recalls funerary sculpture. And the owl and the raven carry morbid connotations. In Shakespeare’s Macbeth, written c. 1605, both birds are mentioned as ill omens and portents of death.

In Salvator Rosa’s L’Umana Fragilità in the Fitzwilliam, detail left [PD.53-1958], the owl that stares out of the shadows undoubtedly carries intimations of mortality. Perhaps van den Broeck’s painting bears a similar message: behind the carefree happiness of youth lies the chilly obscurity of death.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

H.M. Hardcastle; Christie's sale, 12 November 1948, lot 70 (as J. van Hemessen); Arcade Gallery, London; L.C.G. Clarke

Legal notes

Bequeathed 1960.

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Bequeathed

- Dates: 1961

Maker(s)

- Broeck, Crispin van den Painter

Materials used in production

Read more about this recordOther highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…