Wounded Soldiers in a Cart

They were not living troops as seen in war,

But merely phantoms of a dream, afar

In darkness wandering, amid the vapour dim, - A mystery; of shadows a procession grim,

Nearing a blackening sky, unto its rim.

Victor Hugo, 'The Retreat from Moscow', 1852

In 2001 construction workers in Lithuania uncovered a mass grave containing the bones of 2,000 young men. Remnants of clothing identified them as casualties of one of history's greatest military catastrophes, the retreat of Napoleon Bonaparte's Grand Army from Moscow in the winter of 1812.

In June of that year, Bonaparte had crossed the River Niemen onto Russian soil with a pan-European army of around half a million men. It is estimated that only 10,000 of these survived the extreme cold, the hunger and the murderous attacks of Cossacks on their journey home. Here Théodore Géricault, who himself served as a cavalryman in Napoleon's army after the Russian campaign, registers the shock felt in France by her army's unprecedented failure.

What a contrast these wretched travellers make with the Officer of the Hussars on Horseback, the work that first bought Géricault to public attention in 1812. This dramatic canvas, left, is now in the Louvre, Paris.

As with the bodies found in Lithuania, it is only a few details of costume that allow us to recognise these pale, weary figures as members of the hapless Napoleonic army. The once proud blue of the uniforms is faded to a dusty grey. The soldier in the foreground, his back turned to the viewer, wears the tall bearskin hat of the elite Imperial Guard, but the red rosette on the fur, once the sign of his elevated status, now resembles a raw wound. The man on the left in helmet and boots is a cavalryman, his horse, one presumes, long dead.

Like the troops in Victor Hugo's account of the disaster quoted above, these men are shadows of the warriors who marched so confidently into Russia. It is impossible to tell how many casualties are being transported on this cart: towards the back of the picture the passengers become an indistinct, blurred mass, in which a single, haunted face is just visible.

Indeed the only facial features that can be seen with any clarity are those of the man being lifted by his colleagues. His face and neck are the most brightly lit part of this largely dark composition. His skin is sickly and pale, tinged with green. His mouth hangs slightly open and his eye is sunken.

It could be that this is a wounded soldier being helped onto the wagon by his colleagues. But given his lifeless expression and the arm that hangs limp in the centre of the canvas, it is more likely that he is dead already, a corpse being taken down from the wagon to make room for the living, one of the thousands who were left unburied at the side of the road during the long retreat.

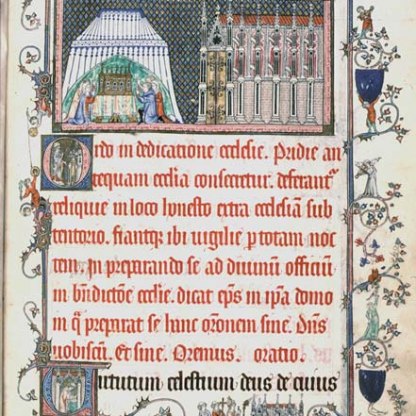

His posture and those of the men lifting him recall scenes of the descent of Christ from the cross. The figures of Joseph of Arimathea, Nicodemus and Christ in a drawing by the sixteenth-century Italian artist Belisario Corenzio in the Fitzwilliam, left [PD.150-1994], closely resemble the three central soldiers in Géricault's work. It is as if the French painter is elevating his doomed countrymen to the status of martyrs.

In its subject-matter – a group of wounded men desperately fighting for survival – this small painting resembles the huge work painted in 1819 for which Géricault is still best known today: The Raft of the Medusa, left, now in the Louvre, Paris. This too takes a contemporary disaster as its theme: the plight of shipwrecked sailors, left adrift for twelve days off the coast of Senegal in 1816. It is an extraordinary, harrowing image, and perfectly exemplifies the mixture of realism and Romanticism which ensured that Géricault, despite his short life, exercised a profound influence on the art of the nineteenth century.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

Sauvé; Tabourier; de Beurnonville; Thiébault-Sisson; Duc de Trevise [not checked]

Legal notes

Bequeathed by A.J. Hugh Smith through the National Art-Collections Fund, 1964

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Bequeathed

- Dates: 1964

Dating

Maker(s)

Materials used in production

Read more about this recordStories, Contexts and Themes

Other highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…