The events of the wars and settlements between European settlers and the Maori peoples of New Zealand remain controversial: cases for millions of dollars worth of compensation are still sub judice and expropriations of Maori land under laws now considered reprehensible by the government continued even as late as the 1960s. Naturally, those whose livelihood depends on such matters have been active in the historiography of the conflicts, and it is hard for the outsider to comment with full understanding. It is often clear, however, that one reason that conflicting accounts of the process can be maintained is that although neither British nor Maori acted as a single interest group at almost any time, their opponents often presumed, through ignorance or convenience, that the other could be treated as such a group. This problem, crystallised in the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, has persisted ever since.

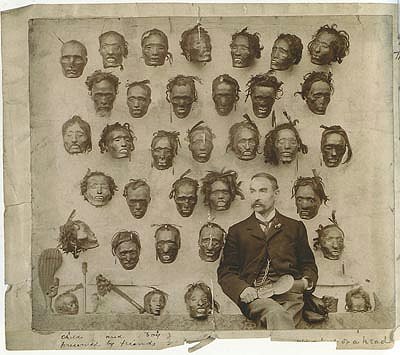

A nineteenth-century collection of preserved Maori heads that went on to form part of the Wellcome Collection, image reproduced from S. Percy Smith, Maori Wars of the Nineteenth Century (Christchurch 1910)

New Zealand became a destination for settlers from Europe, most especially Britain in the North Island and France in the South, from the 1800s onwards, as whalers and trappers began to exploit its resources and harbours by dealing with the Maori peoples to obtain goods for resale in New South Wales or further afield. One consequence of this was the importation of Christianity to the islands by missionaries. These found the Maori a readier audience for their message than the Europeans, whose settlement at Kororareka was described as a 'hell-hole'. One result of such contact was a Roman transcription of the Maori language, which was eagerly adopted by many of its speakers. Another less happy consequence was the importation of fire-arms, often traded for preserved and tattooed heads of enemies in wars against other tribes which the muskets exacerbated. The conflicts between tribes, known as the Musket Wars for obvious reasons, along with diseases imported unwittingly by the Europeans, significantly debilitated the Maori population during the 1820s, while European settlement increased.

Paihia Mission Station, Bay of Islands, in 1827, image reproduced from S. Percy Smith, Maori Wars of the Nineteenth Century (Christchurch 1910)

Outbreaks of violence were inevitable in this situation, and reprisals ineluctable. Suspicion between Europeans and Maori was increased by the practice of selling Maori land to the Europeans for settlement. There is some truth in the view that says that the Maori, for whom all land was commonly held by the people, did not understand these sales as any more than the short-term renting of the right to use the land; they would therefore sometimes sell land multiple times to several new owners. The Europeans of course considered such sales full transfer of property. In some cases, however, it seems likely that either or both sides were aware of the other's understanding and did not expect to fulfil it.

Kororareka Beach (now Russell) in 1827, image reproduced from S. Percy Smith, Maori Wars of the Nineteenth Century (Christchurch 1910)

Cases where violence affected Europeans increased as the number of Europeans did, and these made it clear that New Zealand at this time lay beyond the law. The British colony of New South Wales exercised some influence but had no official jurisdiction over the settlers in New Zealand. Neither Maori nor Britons could expect legal redress for wrongs against them except that which they could broker locally. In the North Island this led both Britons and Maori to appeal to the British Crown for help: a Maori embassy was heard by King William IV in 1831, and a British Resident correspondingly installed in 1833. He had little power, and saw his only hope of effect in organising the Maori; the consequent Declaration of Independence by 52 Maori chiefs in 1835 was however presumably not what the Crown had had in mind and was ignored for all practical purposes. The British government was, however, genuinely keen to prevent and redress the expropriation of the Maori by ungoverned British subjects as well as the protection of its interests, and by 1839 had decided on annexation, not least because French plans to act similarly with the South Island were in the air. Also, private individuals had meanwhile formed a New Zealand Company with the project of buying and settling as much land as possible so as to establish an unassailable position there. In 1839, therefore, William Hobson was therefore sent to New Zealand as Consul with a brief to obtain sovereignty of the islands for the British Crown.

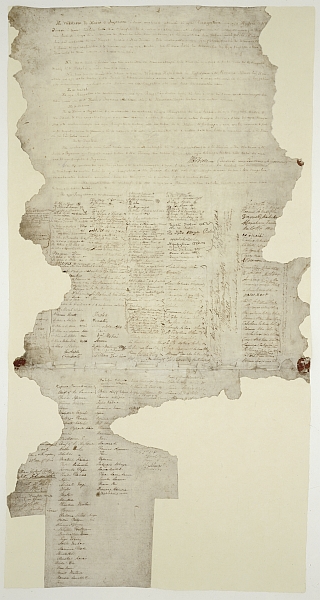

First sheet of the Treaty of Waitangi, National Archives, Wellington, New Zealand, image reproduced under Crown Copyright

The result of Hobson's intervention was The Treaty of Waitangi. The Treaty has become the touchstone of the accommodation between British and Maori peoples in New Zealand, and it is the legal basis on which claims for compensation now rest, administered by a Tribunal set up in 1975. Its importance in 1840 was however very shortlived. Hobson was able to convince a number of Maori chiefs that their safety lay in allowing Queen Victoria to assume dominion over the North Island, and therefore her subjects therein against whom justice might then be pursued. He also promised restitution of illegal or unjust land appropriations, and equal rights under the law for the Maori and British. How far the Maori chiefs understood that this would mean a demotion of their own customs in favour of a British law they did not know, or that they would lose some rights over their own peoples, is debated. It is certain that while some chiefs saw safety in the Treaty and some saw a great increase in mana (roughly, standing) in their association with the distant queen, others were reluctant to sign and did not understand what the British thought they had done, something which was quite clear to the British at the time. Issues of translation between the Maori-language treaty signed by the chiefs and the English-language version recognised by the Crown further complicate matters: the British term 'sovereignty' had to be glossed in Maori with a word closer to 'governance', for example. Also, although many chiefs did sign, some in a subsequent tour made by Hobson with a copy of the Treaty, plenty did not, and the South Island was annexed in 1840 'by cession' with no such show of agreement. (Stewart Island was similarly acquired 'by right of discovery'.) Hobson was then able to declare the islands as subject to the British Crown and was appointed Lieutenant-Governor.

Oil painting of William Hobson by James Ingram, 1913, Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, G-826-1. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any re-use of this image.

Although his correspondence indicates that he expected the Maori to die out before long, Hobson's intents towards them may have been sincere: even before the treaty negotiations he halted all land purchases until previous ones could be investigated, and tribunals to investigate land purchases were duly set up in 1842, though the Lieutenant-Governor, who died that year, did not live to see them in action. Rather than return lands to the Maori direct, however, the tribunals assumed illegally-appropriated land to the Crown, and granted back allowances of, at maximum, 4 acres, to the plaintiffs. Many purchases by the New Zealand Company, furthermore, were found illegal but not reclaimed. In 1842 it was declared that even Maori who had not signed the Treaty of Waitangi were bound by it, and in 1844, pressured by both settlers and Maori, the provision of the Treaty that only the Crown could buy land from the Maori was waived by the new governor. Disputes over tribunal findings had continued meanwhile, and violence had already broken out in several places. War was only an escalation away.