The Three Crosses

And it was about the sixth hour; and there was darkness over the earth ... and when Jesus had cried with a loud voice, he said, Father, into thy hands I commend my spirit: and having said thus, he gave up the ghost.

Luke, 23, 44–6

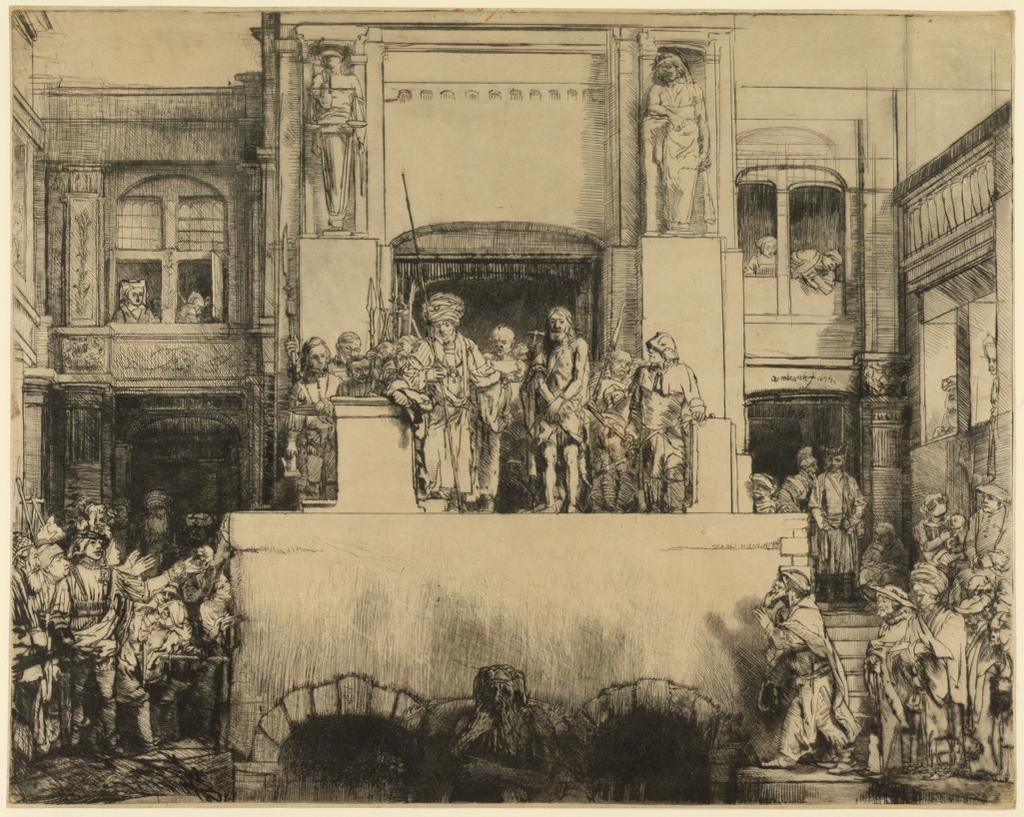

In this print, one of the finest ever made, the Dutch artist Rembrandt imagines the very moment of Christ’s death upon the cross. It is a masterful image, with its complex and crowded composition, its startling evocation of light and shadow. And although there is no mistaking the divine significance of the event depicted, Rembrandt has created a poignant human drama.

Over thirty figures populate Calvary, the hill outside Jerusalem where the Crucifixion took place, but not all of them acknowledge or appreciate the significance of what is happening.

Deep black ink overwhelms the outer edges of the scene: in the cave mouth that gapes to the lower right, in the areas immediately behind the two thieves crucified alongside Christ, and in the mass of figures to the left who turn their backs on the dying 'light of the world'.

In the middle foreground two turbaned figures hurry away from the execution, apparently oblivious of the drama unfolding behind them. They might be representatives of the 'chief priests, and captains of the temple, and the elders', who, according to Luke, 22, 52, had been responsible for Christ's arrest.

While these two ignore the death behind them, their dog, trotting at their heels, glances up at the cross which is bathed in a flood of bright, harsh light. Nearby a woman has fallen onto her face, as much to hide her eyes from the unearthly brightness, perhaps, as to do reverence to Christ.

Those around and between the three crosses are almost bleached out by the pyramid-shaped shaft of light from above, and Rembrandt has depicted them with the simplest strokes of the drypoint stylus. To the right of Christ’s cross as we look at it, members of his family and disciples have gathered. His mother Mary has collapsed and is attended by several women. A young man, the apostle John, raises his hands to his head in anguish.

On the other side of the cross, opposite the swooning Virgin, a man in armour kneels with his back to the viewer, gazing at the crucified Christ, spreading his hands in wonder and worship. It is the Roman soldier who is said, in Luke’s Gospel, to have acknowledged Christ’s divinity at the moment of his death: 'Now when the centurion saw what was done, he glorified God, saying, Certainly this man was righteous.'

And here, perhaps, is the sense of hope within the print: Christ’s death has led to the immediate conversion of a pagan, a soldier in the imperial army. It is significant that many of the early Christian martyrs came from the ranks of the Roman army. This body of men, stationed throughout the empire, were instrumental in the spread of Christianity.

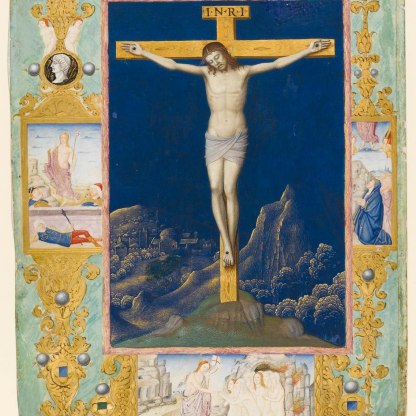

This is the third state of the print, and the first one that Rembrandt signed, suggesting that he regarded it as finished. But within a few months he was to work the copper plate again, in an extraordinary way. The fourth state, illustrated left [AD.20.15-9], transforms the composition into something much more sombre, much more bleak. Though this state was made last, the narrative has gone back in time. It is the moment when, alive and in agony, Christ cries out to his father, 'My God, My God, why hast thou forsaken me?'

He is a lonelier figure here than in the earlier state, for Rembrandt has engraved heavy lines which obscure much of the detail, and has redrawn several of the figures. St John spreads his arms wide now, in grief-stricken sympathy with his crucified master. The converted centurion has been replaced by an impassive mounted figure. The heavenly light has been almost entirely replaced by sharp streaks of darkness.

Rembrandt radically reworked copper plates at other times in his career. Below are two states of his 1655 print Christ Presented to the People.

In the first [AD.20.15-2], Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judaea, addresses a crowd in front of his balcony, and asks them to judge the bound Christ.

In the second [23.K.5-130], the crowd directly in front of the balcony has been deleted, and replaced with a mysterious bearded figure. Christ and Pilate now address the viewer of the print directly. We are, ourselves, implicated in the judgement and condemnation of Christ.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Transferred

- Dates: 1876

Dating

III/V. Printed on Oriental paper.

- 1650s

- Production date: AD 1653

Maker(s)

- Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn Printmaker

Note

III/V. Printed on Oriental paper.

Materials used in production

Read more about this recordStories, Contexts and Themes

Other highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…