The Deposition

The conditions in which these people live are appalling ... The state of their minds is plainly written on their faces, as starvation has reduced their bodies to skeletons ... They must die and nothing can save them – their end is inescapable, they are too far gone now to be brought back to life.

A British soldier witnessing the liberation of Belsen, April 1945

One of the inspirations behind Graham Sutherland’s harrowing image of Christ’s descent from the cross was a booklet of photographs which showed victims of the Nazi Holocaust. The biblical characters in this painting – Christ, the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene, Joseph of Arimathea – are presented as malnourished victims, their flesh lifeless, their faces skeletal, like the Jews who emerged in April 1945 from the Belsen concentration camp.

But while the horrified British soldier quoted above saw the inmates of Belsen as ‘too far gone now to be bought back to life', Sutherland, by placing them in the context of Christ’s Crucifixion, suggests that even in the bleakest moments of suffering, there is hope. The artist, who had become a Roman Catholic in 1926 so that he could marry his wife Kathleen, explained in 1952:

the Crucifixion idea interested me because ... it is the most tragic of all themes, and yet inherent in it is the promise of salvation. It is the symbol of the precarious balanced moment, the hair’s-breadth between black and white.

On the ground at the right of the cross here is a stylised representation of the skull of Adam, a feature found in paintings of the Crucifixion since the ninth century. We see it, for example, in Cosimo Tura’s fifteenth-century panel in the Fitzwilliam [PD.30-1947].

The traditional motif is treated here, however, in an entirely modern way. Sutherland – who prior to 1946 had rarely painted the human figure – drew inspiration from the cubist heads of Pablo Picasso, like that from the Fitzwilliam collection [PD.13-1974].

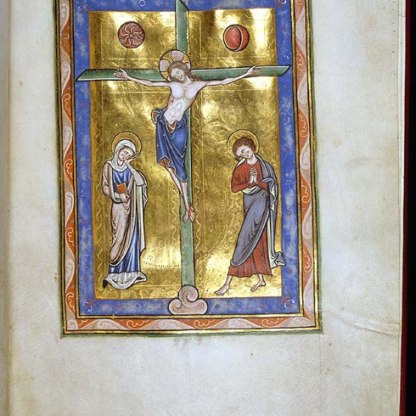

The influence of Picasso is also felt in the figures of the women, particularly Mary Magdalene, who clings to the bottom of the cross, breast bared, head thrown back. Blood from the wounds in Christ’s feet stains her hands. Much of this is, again, traditional – she appears in a very similar position, for example, in an early fourteenth-century panel in the Fitzwilliam by the Master of Verucchio, right [PD.8-1955]. But, in Sutherland’s painting, she is almost dehumanised by her grief. Her eye is a mere black slit. Her mouth is set in a lipless grimace.

Mary the mother of Christ, as ashen as the corpse of her son, reaches up to embrace him, her eye also a mere smudge of black. Her blue garment with its gold trim is a touching reminder of so many images of the Virgin and Child, such as that by Luca di Tommè [563].

Facing Mary, and supporting her son’s body, is Joseph of Arimathea, the wealthy Jew who helped to bury Christ. The small face that stares out and seems to emerge from the bar of the cross, detail right, probably represents Nicodemus, who with Joseph, according to the Gospel of John, 'took the body of Jesus, and wound it in linen clothes with the spices, as the manner of the Jews is to bury'.

It is interesting to note, when looking at this Holocaust-inspired image, that the Jewishness of Christ is highlighted in the biblical accounts of the Deposition: St John stresses that the body was prepared for burial in 'the manner of the Jews'. The Russian-born artist Marc Chagall also painted images of the dying Christ to describe the plight of the Jews in Europe in the 1930s. The imagery of the Crucifixion, which had for centuries been used to justify or promote anti-Semitic feeling was, tragically but to great effect, suddenly being viewed in a Jewish context.

Sutherland’s Deposition was painted at the same time as a larger Crucifixion that had been commissioned for a church in Northampton. Both works are among the most immediately horrific images of Christ’s suffering ever painted. But they draw inspiration from the remarkable Isenheim Altarpiece, painted by the German artist Matthias Grünewald in the sixteenth century. The browns and greens and the square of red in the background of Sutherland’s painting are perhaps abstracted from this extraordinary work. The Isenheim Altarpiece was made for a plague hospital in Alsace: like Sutherland’s, Grünewald's Christ, by promising to survive the agony of crucifixion, offers the hope of personal salvation.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Bequeathed

- Dates: 1963

Dating

- 1940s

- Production date: AD 1946

Maker(s)

- Sutherland, Graham Vivian Painter

Materials used in production

Read more about this recordStories, Contexts and Themes

Other highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…