The Descent From The Cross

Graham Sutherland’s post-Second World War depiction of the removal of Christ’s body from the cross shows a remarkable continuity with earlier, medieval and Renaissance versions.

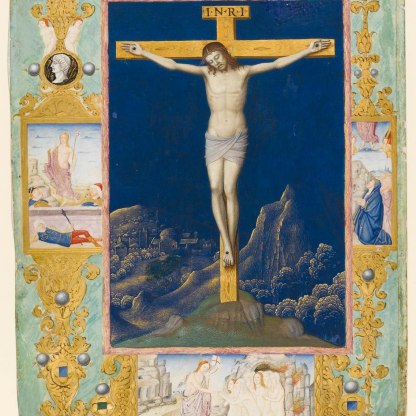

An illumination from an early fifteenth-century French Book of Hours shows the Descent [MS.62.f.134r]. As in Sutherland’s painting, the nails here have already been removed from Christ’s hands and his body is being gently lowered. His mother reaches towards him, poignantly kissing her son’s lifeless hand. Behind her stands St John and other haloed followers. Mary Magdalene clings grief-stricken to the bottom of the cross.

On the ground, a man removes the nail from Christ’s feet with a pair of tweezers. This is Nicodemus, mentioned in John’s Gospel, 19, 39, as one of those who helped bury Christ’s body. Up a ladder, easing Christ towards his followers below, is Joseph of Arimathea, the wealthy Jew and secret follower of Christ who persuaded Pontius Pilate to allow him to take Christ’s body for burial. In contrast to Nicodemus, Joseph is often represented richly dressed and with a hat. Here a moneybag hanging from his belt indicates that he is a man of wealth. On the ground, another finely attired figure holds the nails that have been removed from Christ’s hands.

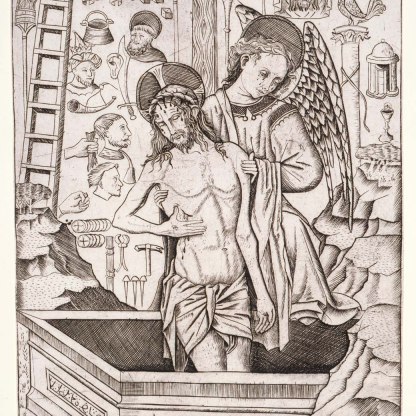

There was a medieval tradition that the Virgin Mary shared in the agony of her son upon the cross. Above is a fifteenth-century drawing in the Fitzwilliam [2272], a sketch of the central panel of a now lost altarpiece by the Flemish artist Robert Campin. Here the Virgin swoons and is held up by St John, a close parallel to her son’s limp body, which is also supported by a male figure, probably Nicodemus.

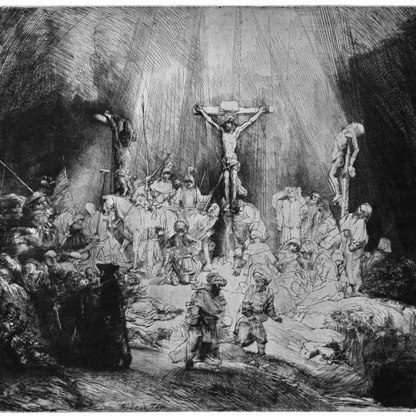

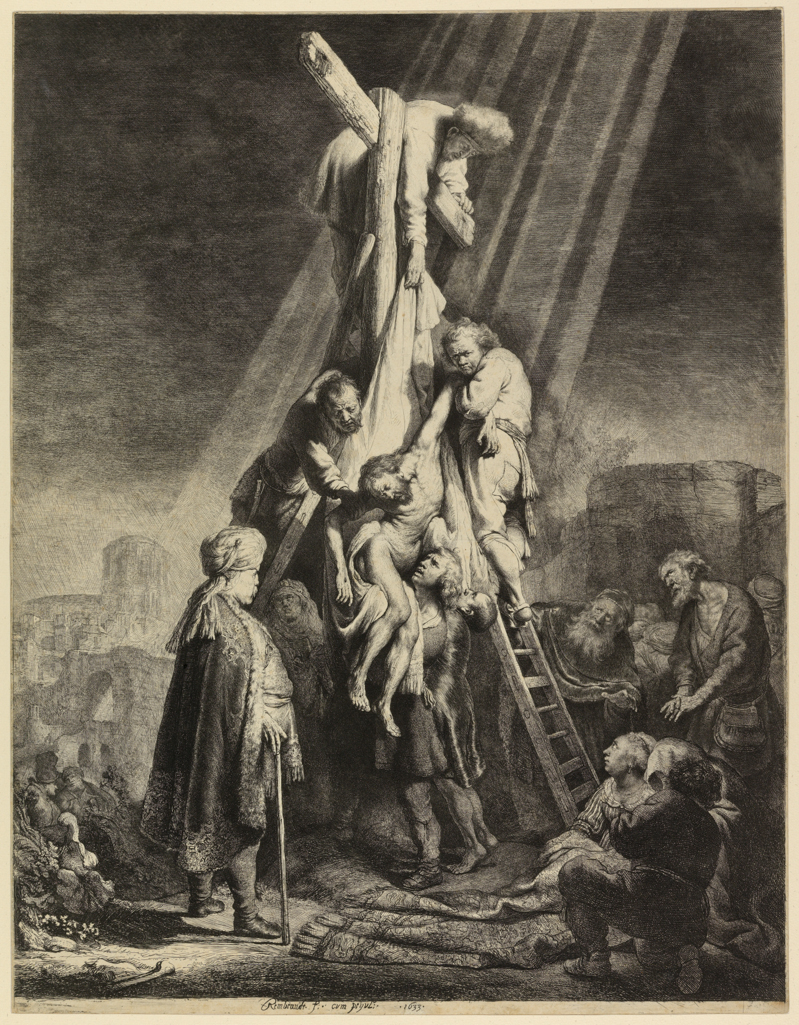

A print by the seventeenth-century Dutch artist, Rembrandt [P.2270-R], suggests the physical difficulty of removing a dead body from a cross. Here a white sheet has been used to cradle Christ as he is lowered. His body twists awkwardly, its dead weight suggested by the exertions of the five men involved in the operation. A portly Joseph of Arimathea looks on. This print is based upon a painting by Rembrandt which was itself inspired by an altarpiece made c.1612 by Peter Paul Rubens for Antwerp cathedral. The man holding Christ’s outstretched arm and frowning out at the viewer in Rembrandt's print is thought to be a self-portrait.

A drawing [PD.150-1994] by the Italian painter Belisario Corenzio, who was active in Naples between 1590 and 1646 shows that Christ’s entire body has already been removed from the cross, and Joseph and Nicodemus are carrying it, before laying it on the ground and wrapping it in its shroud.

The removal of Christ from the cross is usually called the Deposition, though strictly speaking this word refers the laying of his body on the ground. We see this taking place in the central panel of an anonymous early sixteenth-century, probably French, altarpiece in the Fitzwilliam [M.25]. Here the central figures that we have seen elsewhere helping take the corpse of Christ from the cross kneel in reverent sorrow. The crown of thorns lies on the ground, while a bearded figure standing over Christ holds the three nails.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…