Cupid and Psyche

'We must persuade our young men to take wives. With reasons, with blandishments, with prizes, and with every argument, effort and skill.' (Alberti, On the Family, c. 1440)

In both function and subject matter, Jacopo del Sellaio's colourful and busy panel stresses the importance of marriage in fifteenth-century Florence. It was through marriage that families attained or held on to power, businesses flourished and alliances were made. The social, and frequently political, importance of the institution meant that marriages were celebrated publicly as well as privately.

Special marriage chests – cassoni – were commissioned to commemorate a union, symbols of a family's wealth and status that were paraded through the streets to the bride's new home. A nineteenth-century reconstruction in the Fitzwilliam Museum, [M.29], shows what an entire cassone would have looked like.

Jacopo del Sellaio's panel comes from just such a marriage chest. It illustrates the first half of an ancient romance in which the mortal princess Psyche is mysteriously married to the god of love, Cupid. Below you can see the matching panel which completes the story. It is now in a private collection.

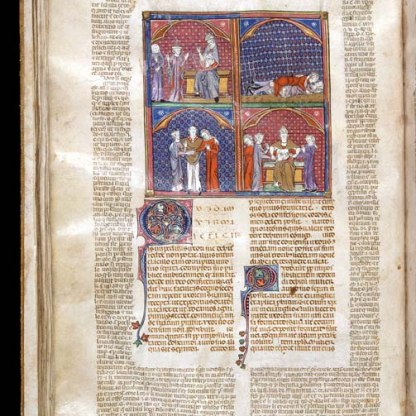

The Fitzwilliam panel depicts the very journey that took place during a Florentine wedding: that of the bride from her father's house to the home of her new husband. Two bedchambers 'bookend' the action: that in which Psyche is conceived and born, left, and that which contains the marital bed, right.

Fifteen distinct episodes from the story appear. Many of these involve the same characters and yet all take place against a single background, within a single landscape. Psyche herself appears eleven times – ten as a full-grown beauty and once as a new-born child. This method of visual storytelling is called 'continuous narrative' and, like the tale of Cupid and Psyche itself, it is based on classical models. The convention is commonly found on Roman sarcophagi.

Today, accustomed as we are to looking at photographs, we usually associate a single pictorial field with a single moment in time. The appearance of the same figure in the same scene, not divided by frames, might appear illogical. In the eighteenth century, James Barry, the President of the Royal Academy in London, criticised as '"defective" [those] old painters who employed different points of time in the same view'. But in Renaissance Italy, continuous narrative was a much more familiar convention. We see it, for instance, on a sixteenth-century maiolica dish in the Fitzwilliam [EC.30-1938]. This depicts another classical love story: Peleus' unconventional wooing of the nymph Thetis.

Though the narrative might, at first glance, appear confusing, the story is read straightforwardly from left to right like a contemporary cartoon strip, and Sellaio arranges the action within a careful, symmetrical composition.

The hovering figure of Cupid on the viewers' left is balanced by the figure of Psyche being wafted from her mountain on the right.

The suitors who approach Psyche's house on the left correspond to Psyche and her sisters outside Cupid's palace on the right.

What would the story of Cupid and Psyche have meant to those who first looked upon this panel? The most frequent viewers would have been the couple whose wedding the cassone was made to celebrate, and it can be seen simply as a pleasing tale about the triumph of love over adversity. There is a clear moral too and the story can be read as a call for obedience within marriage, directed particularly at the wife. Psyche learns through her suffering and becomes an exemplum virtutis – an example of virtue – who should be imitated.

But the Renaissance intellect, steeped in the Greek and Roman classics, went deeper than that. Psyche is itself the Greek word for 'soul', and the story was invested with a philosophical significance. When asked to elaborate upon its precise meaning, Giovanni Boccaccio, the fourteenth-century poet who had retold the tale, pleaded that a full explanation would require too huge a volume. In brief, he explained that it symbolised the quest of the rational soul (Psyche) to be united with Divine Love (Cupid) - an idea found in Plato, and adapted by Christian thinkers in Renaissance Europe.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

One of a pair of cassone panels

Cardinal Joseph Fesch (d. 1839) sale, Rome, 17 March ff., 1845 (1219); Davenport Bromley coll. by 1854; late Rev. Walter Davenport Bromley sale, Christie's, 12-13 June 1863 (60), bt. Roe; late Alexander Barker sale, Christie's 21 June 1879 (486)

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Bequeathed

- Dates: 1912

Maker(s)

- Sellaio, Jacopo del Painter

Materials used in production

Read more about this recordAudio description

Other highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…