The Great Belzoni (1778–1823)

Belzoni is a glorious instance of what singleness of aim and energy of intention will accomplish ... by his indomitable energy he has attached his name to Egypt forever ...

From the diary of Benjamin Robert Haydon, 1821

Giovanni Battista Belzoni was born in Padua, Italy. After an unhappy love affair in his teenage years, he joined a Capuchin monastery, where he studied hydraulic engineering. In 1798, however, when Napoleon invaded Italy, Belzoni fled the country. After four years in Europe, having failed to make a living as an engineer, he arrived in London and embarked upon an entirely new career, as a theatrical strongman.

Belzoni was a hefty 6' 7" (over 2 m), and under his stage name, ‘The Patagonian Samson', he astounded audiences at the Sadler's Wells theatre with his feats of strength. The highlight of his act involved lifting and carrying around the stage a specially constructed frame on which twelve grown men sat.

He left England in 1812, appearing on stage in Portugal, Spain and Malta. In 1815, he went to Egypt, where he offered his services as a hydraulic engineer to the Pasha, Muhammad Ali. His ideas for an ox-driven water pump failed to ignite the Pasha’s interest, but Ali did gave Belzoni a grant to stay in Egypt for a little longer. Intrigued by stories of a mighty carved head lying half-buried in the desert, he applied to the British Consul, Sir Henry Salt, for funds to investigate the possibility of moving this colossus to England. In June 1816 he set off to claim it.

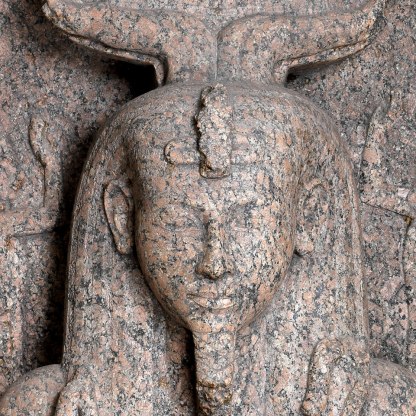

Some time earlier, the French had tried to shift this nine-foot-high granite head – known as ‘the young Memnon’ after a character in Homer’s Iliad. Napoleon’s men had gone so far as to drill a hole in the shoulder of the bust to insert explosives – the fragments, they reasoned, would be easier to move than the whole. Fortunately the plan had not been carried out, and within a few days Belzoni, using the most rudimentary and traditional equipment – levers, wheeled trollies and palm fibre rope – managed to clear the objects in Memnon’s path, move him to the banks of the Nile and put him on a ship to England.

The statue, now in the British Museum, in fact represents Ramesses II, Ramesses III’s great predecessor. At the time, the slight smile on his face was explained by the fact that he was at last going to see England. Inspired by this awesome fragment, in 1818 Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote Ozymandias, his great poem about the transience of power:

I met a traveller from an antique land / Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone / Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand, / Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown, / And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command, / Tell that its sculptor well those passions read, / Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things, / The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed, / And on the pedestal these words appear: / 'My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings: / Look upon my works, ye Mighty, and despair!' / Nothing beside remains. Round the decay / Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare / The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Belzoni had found his vocation, and thereafter he spent several years travelling in Egypt, breaking into tombs, smashing through walls and gathering antiquities on behalf of Sir Henry Salt.

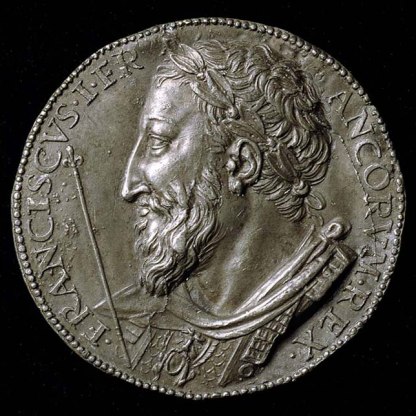

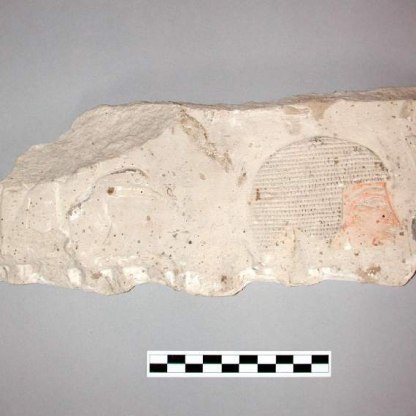

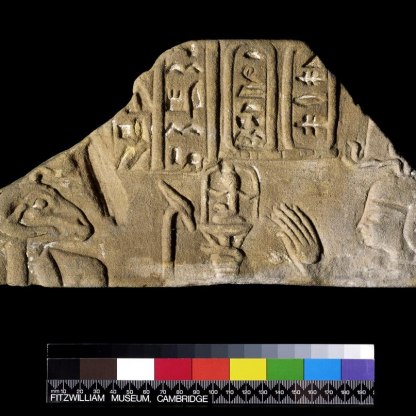

But Belzoni and Salt were not the only Europeans in Egypt hungry for booty from the ancient past. The French consul Bernadino Drovetti was also an enthusiastic collector, and on more than one occasion he and Belzoni found themselves vying for the same antiquities. The two became fierce rivals – during one particularly heated exchange, Drovetti’s men pulled guns on Belzoni and his team. But their relationship had started off on a cordial footing. Having discovered the coffin lid of Ramesses III lying face down in the sand and finding that he was unable to move it himself, Drovetti offered it to Belzoni, shortly after the latter's success with the head of Memnon. In 1817 the huge Italian succeeded in moving the great object. He collected the sarcophagus on behalf of Salt – it is now in the Louvre, Paris. The lid, however, he claimed as his own, later describing it as 'the best piece I accumulated on my own account'.

In 1823, Belzoni, now a celebrity in England, was back in his adopted country to raise money for a proposed expedition to the source of the River Niger. It was then that he donated the coffin lid to the newly founded Fitzwilliam Museum, where it is still a highlight of the Egyptian collection.

Not long afterwards, Belzoni died of dysentery near Timbuktu in Mali, Africa. His methods were far from scientific, and send a shudder down the spines of modern archaeologists. But were it not for his ingenuity, strength and spirit of adventure, the Egyptian galleries of Europe’s great museums would be poorer places today.

Further Reading

- Dawson, W. and Uphill, E. (1995) Who Was Who in Egyptology. Third Edition, revised by Bierbrier, M.L., Egyptian Exploration Society, London, pp.40-41.

- Mayes, S. (1959) The Great Belzoni London.

- Vassilika, E (1995) Egyptian Art. Cambridge, pp.86-87.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…