Men on Horseback

The horse and rider as a symbol of heroism has a distinguished history in Western art stretching back to long before Leonardo’s plans for the monument to Francesco Sforza. In sixth-century BCE Athens, several statues of men on horseback were dedicated in the sanctuary of the goddess Athena on the Acropolis. It is not clear whom exactly these works represent.

They might have been connected with the cult of Athena Hippia – ‘Athena of the horses'. One of the equestrian statues, dating from c. 550 BCE and known as the Rampin Rider, is naked and wears a wreath, perhaps indicating that he was a victor in an athletic contest.

When the Athenians built the Parthenon, the great temple to Athena on the Acropolis, between 447 and 438 BCE, they devoted nearly three-quarters of the 160-foot-long frieze that ran around the top of the building to the depiction of a cavalcade, an army of idealised young men on horseback.

Again, the identity of the riders is uncertain, but a popular theory suggests that they represent the men of Athens who died at the battle of Marathon in 490 BCE: the city is honouring its heroes by depicting them as horsemen. A plaster replica of the Parthenon frieze can be seen around the top of the walls of Gallery 3 in the Fitzwilliam.

In imperial Rome, the emperor was often portrayed on horseback, vanquishing enemies. Left is the reverse of a coin depicting the Emperor Trajan (53–117 CE) trampling down a Dacian foe. Many bronzes of mounted emperors have been lost, destroyed as the Roman world converted to Christianity.

However, one famous statue, of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius (121–80 CE), survives to this day in Rome, where it forms the centrepiece of the Piazza del Campidoglio. The Founder of the Fitzwilliam Museum made a sketch of this monument [3337], copied from a print by the sixteenth-century French engraver Nicholas Beatrizet. The horse raises its front right leg, holding it poised over the recumbent body of a vanquished enemy, now missing.

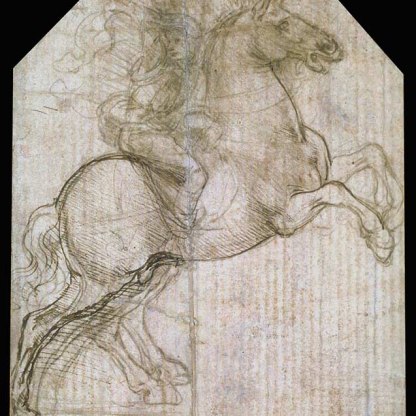

The most celebrated equine statues to have survived from Roman times are the group of four bronze horses that were bought to San Marco in Venice after the Crusaders had sacked Constantinople in 1204. The sketch by Leonardo in the Fitzwilliam, depicting two horses [PD.121-1961], derives the animals’ poses from this famous and elegant quartet. A small bronze in the Fitzwilliam [M.32-1997], made in Venice in the early sixteenth century, is also based upon the horses of San Marco.

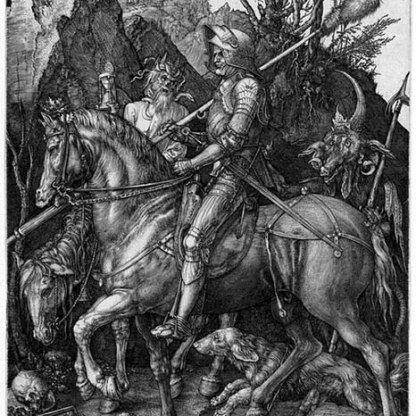

The earliest Christian emperors used the pose of the victorious rider to symbolise victory over their pagan enemies and rivals. The statue of Marcus Aurelius was in fact only preserved because it was originally believed to represent Constantine the Great (274–337 CE), the first Christian emperor. The theme of the rider on a rearing horse was taken up by Christian artists to represent St George fighting the dragon. Left is the reverse of a gold sovereign from the reign of Queen Victoria, showing George, who is also the patron saint of England.

A rider on a white horse might also represent Christ, after the vision of St John mentioned in the Book of Revelation, 19, 11:

And I saw heaven opened, and behold a white horse; and he that sat upon him was called Faithful and True, and in righteousness he doth judge truth and make war.

From the thirteenth century in Italy, the equestrian statue was once more being used to glorify and celebrate political and military leaders. Famous examples exist by the Florentine sculptor Donatello and by Leonardo’s own teacher, Andrea del Verocchio.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…