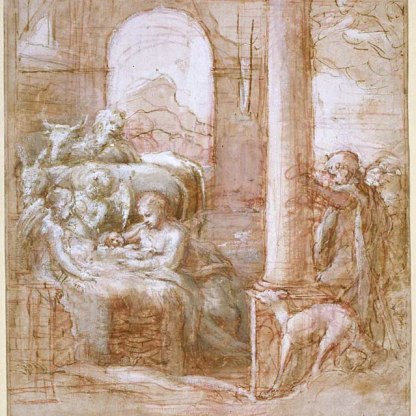

The Nativity

Despite Matthew’s description of the wise men who visited the new-born Jesus entering ‘a house’, artists and writers have tended to place the Nativity and the events immediately following it, in humbler surroundings – a stable, a cave or a ruin, sometimes even a bare hillside. So it is in Domenico Ghirlandaio’s painting, in which a dilapidated roof and a stone wall are the only protection for the Holy Family. There may be an allusion here to the Old Testament – the ancient, obsolete law, a ruin that Christ will renew.

The ox and the ass that so often view the Nativity are not mentioned in the Bible, but as early as the fourth century CE sculptors of Roman sarcophagi included them in scenes of Christ’s birth. Indeed, in the earliest representations, they accompany the Christ Child more frequently than Joseph and Mary.

Medieval writers record that the animals breathed on the holy infant to keep him warm, but a more elaborate interpretation identifies the ox with the Jewish people and the ass with the pagans, who will both bow before the new Messiah.

The Book of Habbakuk in the Old Testament says at 3, 2: 'in the midst of two beasts wilt thou be known', and the Nativity was taken as a fulfilment of that prophecy. Isaiah’s words at 1, 3 were also quoted in reference to the animals in the stable: 'the ox knoweth his master and the ass his master’s crib; but Israel doth not know'.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…