Egyptian Writing

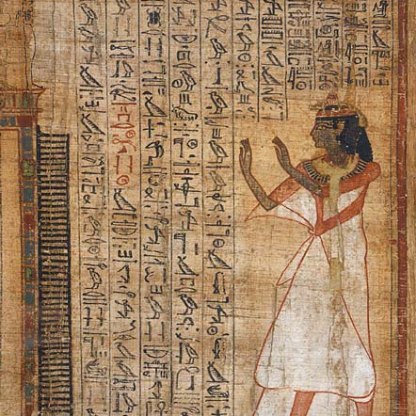

Inpehufnakht’s 'Book of the Dead' is written in black and red ink on a papyrus scroll, a writing surface made from the fibres of the papyrus plant. This tall freshwater reed grew in large quantities along the banks of the Nile. The plant in flower was itself an emblem of Lower Egypt – the area around the Nile Delta. The name for Lower Egypt could be written in hieroglyphs as several flowering papyrus plants growing on land. As a hieroglyphic sign on its own it signifies ‘green'.

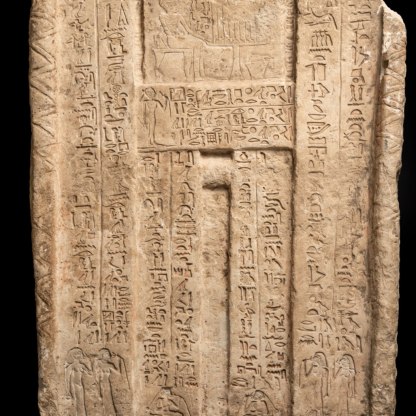

The word 'hieroglyph' literally means ‘sacred carving'. It describes the ancient Egyptian script that consisted of simple pictorial signs arranged in horizontal or vertical lines. Hieroglyphs were used for over four millennia in Egypt, the last known datable inscription being made in 394 CE.

There are three main types of hieroglyphic symbol, each with different functions:

- Phonograms, which represent sounds, like syllables in the English language

- Logograms, which represent objects or ideas

- Determinatives, which appear at the end of words to clarify other words in the sentence

Hieroglyphs could be written from left to right or from right to left (the most common direction on papyri), and either horizontally or in columns, as here. In the part of Inpehufnakht’s papyrus illustrated in the margin, the scribe has struggled to cope with the unfamiliar left-to-right direction. As a result the words of the recitation have become jumbled.

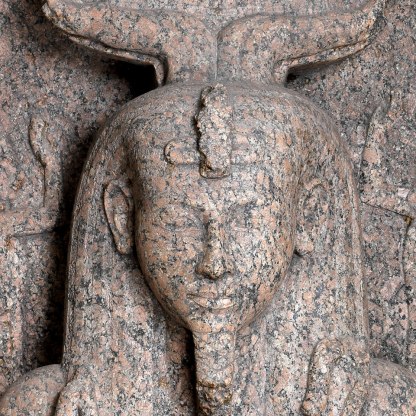

Literacy levels were low in ancient Egypt, and great prestige was attached to the position of scribe. A limestone sculpture in the Fitzwilliam [E.21.1887] shows a scribe called Kerem with his wife Abyky. He proudly holds the tools of his trade – the scribal palette and brush.

The scribe’s palette was usually made of wood, with two depressions to hold the red and black inks, and a slot for the reed pens. A stone palette in the Fitzwilliam [E.428.1982] was made for purely ceremonial or funerary purposes.

Hieroglyphs could not be understood in modern times until the early nineteenth century when a Frenchman, Jean-François Champollion, deciphered them. His decipherment was based upon several monuments, most famously a decree carved in three scripts on a stone slab now in the British Museum – known as the Rosetta Stone, after the village in Egypt where it was discovered.

The same text was written in Greek, Demotic – the everyday script in ancient Egypt – and hieroglyphs, and by comparing the known language, Greek, with the hieroglyphs, the way of reading this ancient pictorial script was slowly revealed.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…