Books of Hours

An Hours of the Virgin must be mine / As it should belong to a woman / Coming from noble peerage ... / Of gold and of blue, rich and elegant

Eustache Deschamps, French poet (1346–1406)

Before the thirteenth century, while manuscripts were produced by and for religious communities, few individuals or families were able to afford their own books. Around 1300, however, when devotion to the Virgin Mary was at its peak, Books of Hours began to be produced in bulk. Lay people from a newly emerged European middle class, people who had never before owned or even had access to books, were now willing and able to buy them. As the fourteenth-century verses quoted above suggest, Books of Hours began to carry considerable weight as status symbols in the late middle ages.

The Book of Hours is effectively a simplified version of the Breviary – a volume containing the prayers and readings around which the life of the clergy revolved. The devotions were based around the eight canonical hours of the day: Matins and Lauds, which were said at daybreak, Prime at 6 a.m., Terce at 9 a.m., Sext at midday, None at 3 p.m., Vespers at sunset and Compline before going to bed. St Paul had enjoined Christians to 'pray continuously', and the imposition of this structure upon the day allowed the faithful to approximate this commandment.

As they were made for lay individuals as well as for monks, nuns and secular clergy, the specific content of different Books of Hours varies enormously. No two are the same, although most share the same core elements.

At the beginning there is usually a Calendar, showing the feast days of the Christian year. Days of particular significance are written in gold or in red – whence the phrase 'red-letter day', meaning a lucky or memorable day. Each month was accompanied by its appropriate zodiacal sign, and by often a miniature showing the work done in that month. Left is the page for May from a sixteenth-century Parisian Book of Hours in the Fitzwilliam [MS.134.f.9r]. A man serenades a woman on a lute, as she sews, in a lush green garden. In the top right, in a blue cloud, the twins of the constellation Gemini embrace.

The Calendar was usually followed by four short readings from the Gospels of John, Luke, Matthew and Mark – in that order. Each reading may be headed by a miniature depicting the appropriate Evangelist. The four images below are from a richly decorated c. 1500 French Book of Hours in the Fitzwilliam illuminated in the atelier (workshop) of the celebrated court painter Jean Bourdichon [MS.131].

- John

- Luke

- Matthew

- Mark

Less lavishly decorated manuscripts might have only a single image of John.

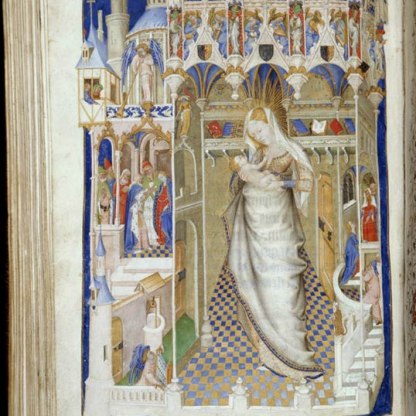

The Hours of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the central text of the book, came next. Each of the eight Hours contain a hymn, usually three Psalms, a short reading and a prayer. In continental manuscripts the text for each Hour was usually headed by illustrations concerning the infancy of Christ, while English patrons preferred scenes from Christ’s Passion.

A scene of the Annunciation to Mary by the Archangel Gabriel usually preceded Matins, which began Domine labia mea aperies et os meum annunciabit laudem tuam ('O Lord, open thou my lips and my mouth shall show forth the praise.') The full-page miniature of the Annunciation from a Book of Hours made in Bruges c. 1520 probably came from this section [MS.294b].

Lauds was usually headed by a picture of the Visitation, when Mary, after the Annunciation, stayed with her cousin Elizabeth, the mother of John the Baptist. Left is the appropriate page from the Rohan Master's manuscript.

Prime is commonly illustrated by a picture of Christ’s Nativity, or of Joseph and Mary adoring the newly born child. The illustration, left, is again taken from the Rohan Master's manuscript.

Terce is usually accompanied by the Annunciation to the Shepherds [Ms.76.f.59v], and Sext usually shows the Adoration of the Magi

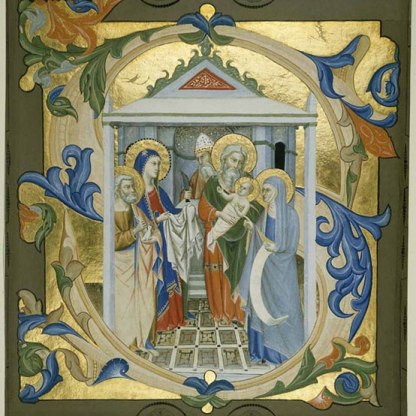

The illustration for None from the Rohan Master's manuscript, depicts the Presentation in the Temple.

Vespers may have the Flight into Egypt [MS.62.f.86], or the Massacre of the Innocents [MS.53.f.68].

Compline usually shows the Coronation of the Virgin [MS.62.f.86] in which Mary is received into Heaven after her death and crowned by the Father, Son and Holy Ghost. Sometimes the Death of the Virgin is shown.

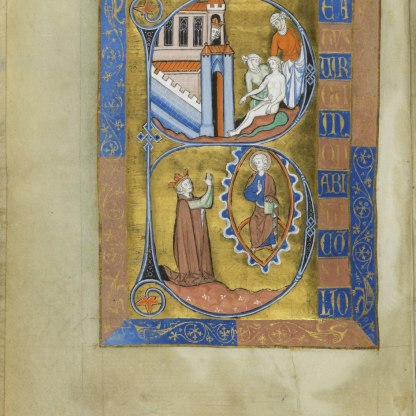

The Hours of the Virgin were central, but other texts often appear in the books. The Seven Penitential Psalms were usually included, and decorated with a miniature showing King David, the supposed author of the Psalms. Left is a particularly fine full-page illumination showing David kneeling, his harp on the ground beside him, as an angel hovers in the air above. It comes from the same c. 1500 French Book of Hours [MS.131] as the portraits of the Evangelists illustrated above.

The Litany usually came next, a list of saints names followed by the words ora pro nobis ('pray for us').

The last text in a Book of Hours was often the Office of the Dead. This was not the Mass for the Dead or the text of the funeral service, but a collection of Psalms and readings originally intended to be said around the coffin of a dead person. It might have also been read by the owner of the book as a reminder of his or her own mortality, suggesting that in such uncertain times, it is well to be prepared for death.

The decoration accompanying the Office of the Dead varied. Sometimes a funeral might be shown taking place, as in the Rohan Hours [MS.62.147r]. In other books the Last Judgment is depicted [MS.294d]. Still others might have an image of Lazarus, whom Christ brought back from the dead in the New Testament.

The illustration [MS.4-1979r] comes from the first page of the Office of the Dead in a fifteenth-century Parisian Book of Hours. It shows the dramatic confrontation between the Archangel Michael and a devil over the soul of a dead man. God the Father looks on from the heavens above.

In the late middle ages, episodes from the Book of Job became increasingly popular at this point. In MS.131.f.236, we see the Old Testament hero seated upon a pile of dung, approached by three women. Another picture sometimes found with the Office of the Dead is called 'The Three Living and the Three Dead' – a legend popular in the middle ages, in which three young men meet their posthumous selves while out riding.

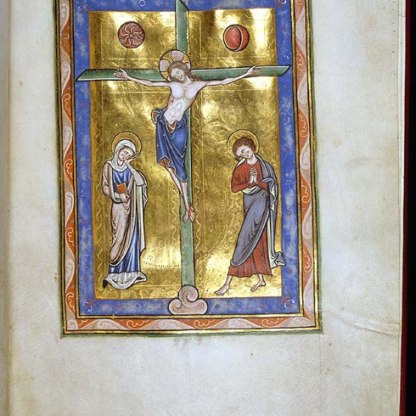

Abbreviated versions of the Hours of the Cross were sometimes included, accompanied by a miniature of the Crucifixion. The Hours of the Holy Spirit might be accompanied by an image depicting the descent of the Holy Ghost at Pentecost [MS.304], attributed to the fifteenth-century French painter and illuminator Simon Marmion.

Almost every Book of Hours contains the two most common prayers to the Virgin Mary, the Obsecro te ('I beseech thee') and O intemerata ('O chaste one').

In addition, short prayers to various saints called 'Suffrages' or Memoriae were often accompanied by images of the saints involved. MS.131.f.356 shows St Francis receiving the stigmata – the wounds of Christ.

Even within those sections common to all Books of Hours, there are substantial textual differences that point to specific geographical areas and allow historians to identify the ‘use’ of the book. The saints commemorated in the Memoriae often give clues to the manuscript’s place of production.

The feasts marked out in gold, red or blue in the Calendar and the saints invoked in the Litany also often give clues to the locality of manufacture or the place where the book was intended to be used. In addition the Calendar may contain the obits – the dates of death – of the owner's relatives.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…