Black, Red and White

Three principal types of painted pottery were produced in Athens between the seventh and late fourth centuries BCE.

The earliest – black-figure – was developed in the Greek city of Corinth around 700 BCE, and was taken up by Athenian pot decorators a few decades later. In this technique, the figures on the vase were painted with an extra fine solution of clay which turned a glossy black during the complex firing process. Details were then incised onto the dark silhouette, while a further limited range of colours might be added. The warm red background is the natural colour of Athenian clay once it has been fired.

Left is a black-figure amphora showing the god Dionysos reclining with his mortal partner Aridane GR.27.1864. The dog beneath the couch and Ariadne herself are painted in white, while the god’s beard and ivy wreath are picked out with an added purplish-red paint. The rib cage and muscles of the boy holding the wine jug, as well as many other details, are incised through the black glaze.

Around 520 BCE, a new technique reversed this scheme. Now the background was coated in black glaze, while the figures within the picture were reserved – that is, left as the natural red colour of the baked clay. Fine black lines within the reserved area were then painted to show drapery, muscles etc, while a dilute black or brown slip might be used to add finer details.

The same period saw the introduction of white-ground pottery. Here a white ground was applied to the clay, on top of which either black-figure or an outline technique was used. Towards the end of the fifth century, a range of colours was often painted onto the clay after it had been fired.

The most common sort of vessel to be decorated in this technique is called a lekythos – a tall cylindrical container for perfume or oil that was often used as a grave offering. Many white ground lekythoi shows mourners at tombs. Wall-painting in fifth-century Athens was a major art form, but no significant examples have survived. These white-ground lekythoi provide us with perhaps the clearest idea of what it may have looked like.

Although many Athenian black- and red-figure vessels were made for the symposium – the Greek drinking-party – most of those on display in museums today were excavated from graves in Italy, put there as offerings for the gods of the underworld or to help the deceased.

The presence of so many black- and red-figure pots in European and American museums is due to their popularity in the eighteenth century. Several now in the Fitzwilliam were brought back from Italy by aristocrats who had collected them during the Grand Tour. They were appreciated for their beauty and treated as works of high art. They also exercised a strong influence on contemporary decorative arts, from pottery to furniture and dress.

In the twentieth century, an Oxford scholar, Sir John Beazley, using methods similar to those developed by connoisseurs of Renaissance drawings and paintings, assigned a large proportion of surviving Greek vases to individuals or workshops. He identified and named many artists, although the majority of vases have no signatures.

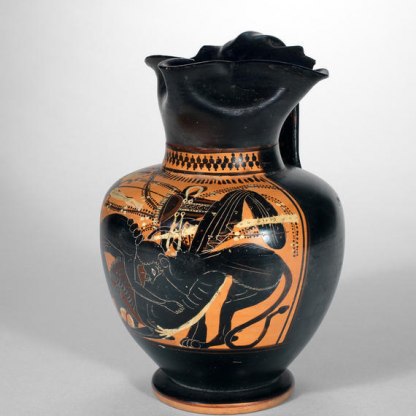

So the painter of a black figure wine jug showing Herakles fighting the Nemean lion GR.7.1937, is named ‘The Red-Line Painter,’ after Beazley noticed several pots that seemed to be by the same decorator, one of whose characteristics was the placing of concentric red lines beneath his compositions.

The painter of the red-figure cup inscribed ‘The boy is beautiful' GR.15.1937, has been called 'The Euergides painter', because Beazley identified his hand on several cups signed by the potter Euergides.

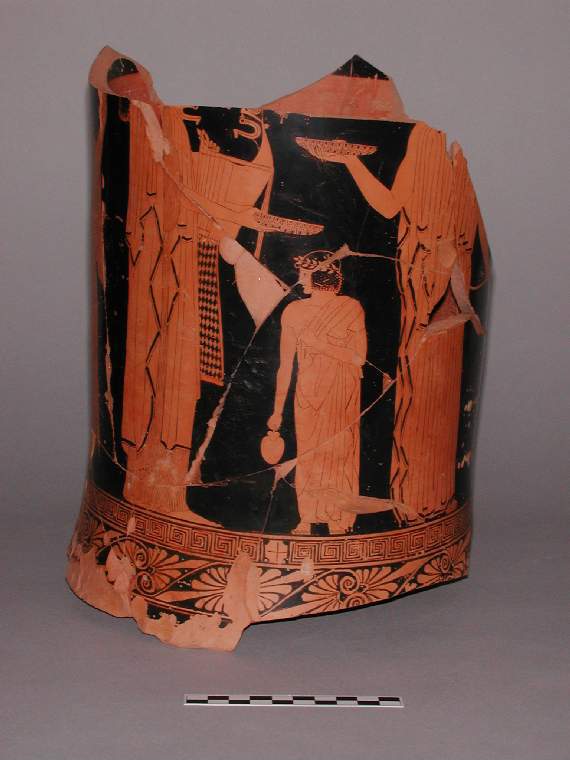

Others pot painters might be named after the museum in which their principle work or works are kept. A fragment from a stand in the Fitzwilliam GR.P.13, is attributed to the 'The Villa Giulia painter', after the museum of that name in Rome.

Nothing is known about these men as individuals, but Beazley's names serve as useful tags under which to group vessels likely to have been decorated by the same hand.

Recently, less emphasis has been placed upon identifying the makers and decorators, and closer attention has been paid to what the vessels can tell us about other aspects of Greek life – religion, myth, athletics, eating and drinking, the daily lives of men and women.

One recent theory has suggested that all red- and black-figure vases are in fact cheap imitations of works in precious metals, and had very little intrinsic value at the time they were made. So the black colour on the pots is made in imitation of tarnished silver, the warm red clay replicates the appearance of gold, the added purple-red slip stands in for copper, and the white for ivory.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…