The Grand Tour – Itinerary

The journey from England to Italy that many well-born young men made in the eighteenth century was not an easy one. Depending upon which combination of land and sea routes was chosen, it could take several months. Travelling was uncomfortable, and the roads dangerous. The English writer Horace Walpole, for example, recorded ruefully how his pet spaniel, Tory, came to a sticky end in the jaws of a wolf while crossing the pass at Mount Cenis, in the Alps between France and Italy. Most travellers were glad to reach Florence, the first great city on the Italian leg of the Tour.

Francois-Xavier Fabre’s 1797 portrait, Allen Smith Seated above the Arno Contemplating Florence PD.16–1984 shows how the typical Grand Tourist wished to be perceived. Smith's pose recalls a celebrated portrait of the German writer Goethe by Johannn Tischbein made in 1786. With his head in profile, like an ancient cameo, and wearing what looks like a Roman toga over his eighteenth-century dress, Smith is surrounded by antiquities. A Corinthian capital lies among weeds at the right of the painting and he leans against a porphyry block bearing (meaningless) Egyptian hieroglyphs. In the distance, we see the bridges over the river Arno, several solid Florentine buildings and, further off, the rolling hills of Tuscany.

The city of Florence itself is not rich in ancient ruins, and there is no Roman site there of any significance. But since the fifteenth century, the powerful Medici family had collected classical antiquities. As a result, Florence was the only Italian city that could rival Rome for the excellence of its ancient sculptures. From the sixteenth century, these were displayed in the city offices, the Uffizi. Among the most celebrated of these ancient works of art was the 'Venus de’ Medici' of which the British writer John Evelyn said, 'nothing in sculpture ever approached this miracle of art'. It remains one of the most admired nudes in the history of art.

In 1743 the last of the Medicis bequeathed the family’s art collection to the city of Florence. Some of the most glorious productions of the Florentine Renaissance were now displayed alongside the antiquities.

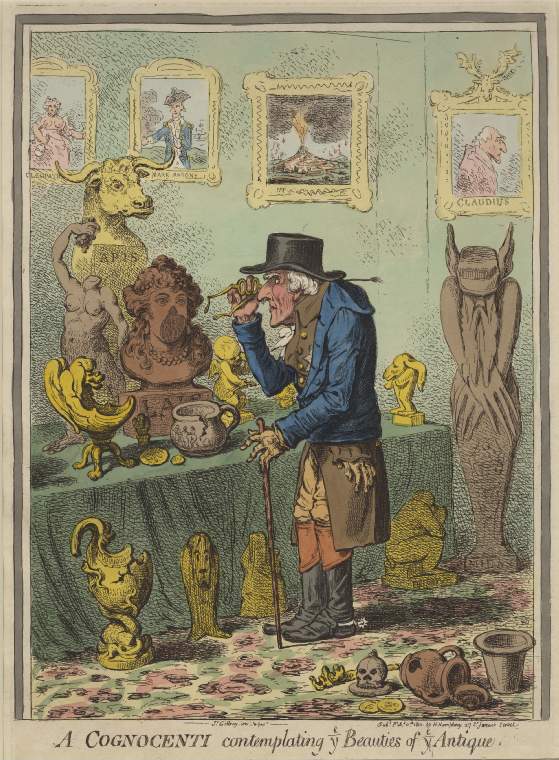

Travellers heading south would often put off a stay in Rome to spend the winter in Naples. A view of this pleasant resort from a book published in 1776 can be seen left. In Naples, the well-connected visitor might be entertained by Sir William Hamilton, the British Envoy and Plenipotentiary at the court of Naples between 1764 and 1800. Hamilton’s great contribution to the history of art was his collection of Greek red-figure vases, which he excavated from graves in southern Italy. Few public collections of antiquities today are without examples of this sort of pottery, and several of the vases in the Fitzwilliam can be traced back to Hamilton’s collection.

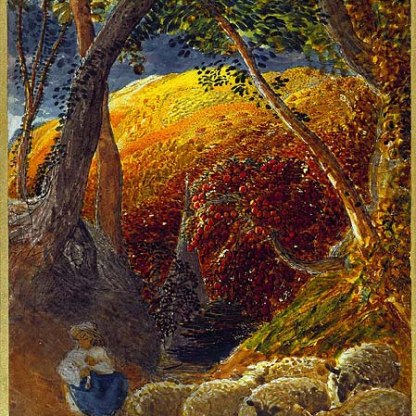

A painting of a volcano in the background of Gillray's cartoon alludes to Hamilton’s other great enthusiasm. He was the guide par excellence for Grand Tourists visiting Mount Vesuvius and the Phlegraean Fields – the volcanic area north of the Bay of Naples. In 1776, he published a lavishly illustrated description of this area, Observations on the Volcanoes of the Two Sicilies, a copy of which is in the Fitzwilliam's Founder’s Library. The plates, such as that left, include dramatic views of Vesuvius in eruption. When the volcano blew spectacularly in 1779, Hamilton published a supplement to his work to commemorate the occasion.

A painting in the Fitzwilliam PD.11-1997, by the French artist Anicet Lemonnier, depicts the great eruption of 1779. Lemonnier must have painted this extraordinary work quickly, in the open air and perilously close to the flowing lava, for particles of volcanic ash are incorporated into the pigment.

The ancient casualties of Vesuvius – the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum – began to be properly excavated in the eighteenth century, and provided an added frisson to the excitement of viewing the great volcano. A watercolour in the Fitzwilliam by the British artist Hugh Williams PD.16-1988, shows the state of the excavations at Pompei in 1817.

It was Rome, however, that usually held the interest of the Grand Tourist for longest. An intensive course in Roman antiquities would last about six weeks, if one spent three hours a day with a cicerone (a guide), but many tourists stayed much longer.

The eighteenth century saw the establishment of the great antiquarian museums of Rome, on the Capitoline and in the Vatican. PD.107-1992 is one of two capriccios by Gianpaolo Panini in the Fitzwilliam which were painted as reminders to Grand Tourists of their trip. These imaginary views incorporate the ancient architectural and sculptural highlights of the great city: the Colosseum, the Arch of Constantine, the Obelisk of Augustus, the Pantheon, the Farnese Hercules (now in Naples) and Trajan’s Column.

Along with the aristocrats, many British artists stayed in Rome in the eighteenth century, to cater to the demands of their art-collecting compatriots. A view of the Villa D’Este, Tivoli, above [1493], by John Robert Cozens provides a reminder of one of the most popular day trips from Rome. An amusing drawing by George Dance in the Fitzwilliam 889(6), shows an enthusiastic young Tourist trying to rouse his laid-back, punch-drinking travelling companions from bed with the words, 'Come, its time to set off for Tivoli'.

The lazy pair in Dance’s drawing would have enjoyed Venice, with its relaxed atmosphere and colourful festivals and regattas. An eighteenth-century observer, John Hinchcliffe, noted that 'if licentiousness is the same thing as liberty, no nation on earth can enjoy an equal freedom with the Venetians'.

The Sala Grande of the Ridotto (PD.1–1980), by Gianantonio Guardi, shows the kind of entertainment popular among tourists in Venice: revellers in masks gamble and flirt. And another painting in the Fitzwilliam by the same artist, PD.22-1952, shows the kind of beauty the adventurous young traveller might hope to find smiling at him from behind a mask at this stage of the Tour.

Although there were no classical antiquities in Venice, the city’s more recent art history was greatly admired, particularly the works of Titian and Tintoretto. And of course the architecture aroused great interest and admiration. From about 1730, Canaletto worked almost exclusively for British clients, via his agent in the city, the merchant and British Consul Joseph Smith. The Founder of the Fitzwilliam owned two works by the artist.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…