The Grand Tour

Sir, a man who has not been to Italy is always conscious of an inferiority, from his not having seen what it is expected a man should see.

Samuel Johnson, 1776

Samuel Johnson, the great eighteenth-century English critic, lexicographer and wit, was writing at a time when an extended trip to Italy was fundamental to the education of young, aristocratic British males.

Italy, and Rome in particular, had been a popular destination for northern European artists, intellectuals and diplomats long before the eighteenth century. The sixteenth-century Netherlandish painter Maarten van Heemskerck presented himself standing proudly in front of the Colosseum a full two centuries before Pompeo Batoni portrayed the young Earl of Northampton on his visit to Rome (shown below – PD.4–1950).

Below is a print in the Fitzwilliam [23.K.2-89] by another sixteenth-century Netherlandish artist who spent time in Rome, Hendrik Goltzius. It depicts, from an unusual point of view, a celebrated statue that was excavated in Rome in 1540, known as the Farnese Hercules. There is a cast of this vast sculpture in the Cambridge University Museum of Classical Archaeology, while the original is now in Naples.

In the sixteenth century, however, most northern Europeans could have only known Italy and its ancient heritage through the work of artists like Heemskerck and Goltzius. The Reformation and the English wars with Spain meant that it was difficult for Protestants to travel in the Roman Catholic south of the continent. Rome itself, as the seat of the pope, was seen as the heartland of the enemy, the home, many thought, of the Antichrist.

What was first referred to as The Grand Tour of France and the Giro of Italy by Richard Lassells in a travel-book published in 1670, did not become an institution amongst the ruling classes of northern Europe until the early 1700s. As Lassells suggests, other countries than Italy were visited – France, the Netherlands, sometimes Germany, and Austria as far as Vienna. In the 1770s, Greece became a feature of the Tour, though the founder of the Fitzwilliam Museum was relatively unusual in going to Spain in search of musical manuscripts.

But Italy was the chief destination and young British men, usually accompanied by a tutor, or ‘bear–leader', might spend several years broadening their intellectual horizons, learning about the country's economics, politics, history and language, in preparation for a career in public life back home. There was less high-minded experience to be acquired too, and it has been said that venereal disease was as much a legacy of the Grand Tour for some English families as the statues in their gardens.

The true driving force behind this secular pilgrimage was the acquisition of ‘taste'. Direct experience and appreciation of classical antiquity and works of the Italian Renaissance would, it was held, polish the character of the English gentleman.

And to show that he had acquired this quality, the Grand Tourist collected antiquities – or copies of them when the originals were not available. Faithful reproductions of ancient sculptures became familiar sights in the parklands of English country houses.

We see, for example, in Sir Joshua Reynold's Portrait of the Bradyll Family in the Fitzwilliam [PD.10–1955], a version of the Medici Vase, one of the most popular works of ancient art in Rome.

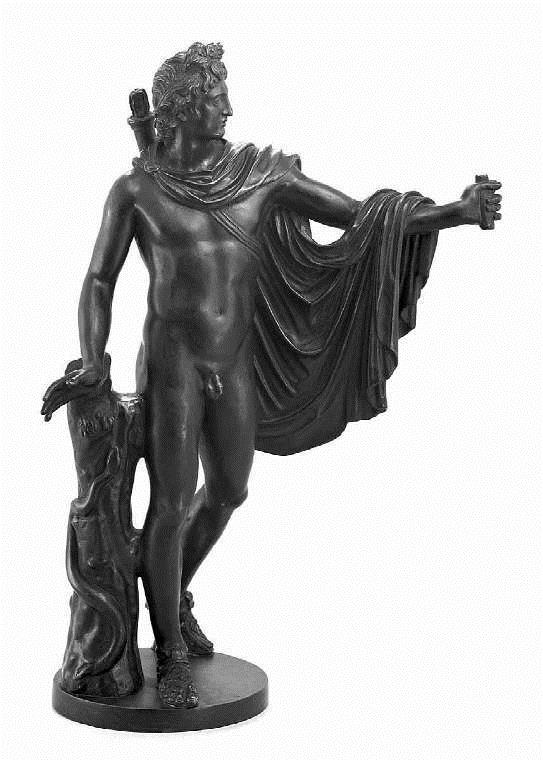

A small eighteenth-century bronze in the Fitzwilliam, above [M.4-1854], is a replica of the Apollo Belverdere, another Roman highlight of the Grand Tour. The original can still be seen on display in the Vatican Museum.

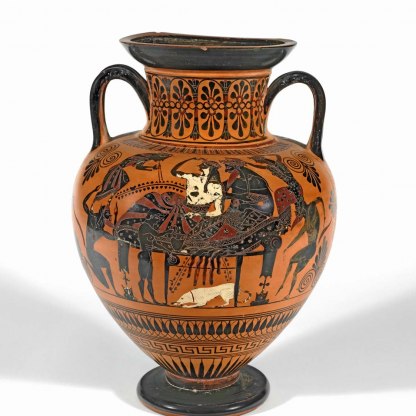

It was, of course, more desirable to own an original antiquity. The Fitzwilliam Museum, with its fine Greek and Roman collections, would not look the way it does today had it not been for the Grand Tour. Many of the ancient sculptures, gems and vases on display were bought to England by returning Tourists as part of their private collections. As taste changed or money grew short, these antiquities were sold and ended up in public museums.

The beautiful head of Antinous, for example, the beloved companion of Hadrian, above [GR.100.1937], was unearthed in the 1770s at Hadrian’s great villa at Tivoli, near Rome. It was bought from a dealer in Rome by William the second earl of Shelburne, who displayed it in the ballroom of his London mansion, Lansdowne House.

The statues in the main entrance hall of the Fitzwilliam Museum are all nineteenth-century copies of ancient works, but the overall effect gives us some idea of what the sculpture galleries of a large eighteenth-century house would have looked like.

Collectors liked their ancient statues to be in as perfect condition as possible, and many damaged works were restored in the eighteenth century. Above, an ancient marble statuette of the Greek god Apollo in the Fitzwilliam [GR.2.1885] is shown restored in Rome by the great British neo-classical sculptor John Flaxman.

This thirst for antiquities led to a sizeable market in fakes. A marble medallion in the Fitzwilliam [GR.63.1850] showing the Emperor Nero crowned as the sun god, was bought as an antique in Venice in about 1752. It was said to have been excavated in Athens, but is in fact cut from Italian marble and was probably made in the eighteenth century to gull a travelling collector.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…