The City

In fifth-century Athens, the greatest artists were set to work beautifying the urban environment and decorating buildings, but no one seems to have made any serious effort to portray the city itself.

Occasionally, individual temples would be schematically depicted on coins, but Athens was generally alluded to in art by the symbolic owl, or an image of the city's legendary founder, the goddess Athena. Both motifs can be seen, left and right, on the two sides of a silver Athenian tetradrachm (a four-drachma coin) dating from c. 450 BCE, in the Fitzwilliam [CM.383-1978].

Although in Rome a wall-painting showing a sophisticated cityscape was recently excavated in the Golden House of Nero, this impressive work seems to be an exception. Architectural elements appear in Roman painting, and buildings and triumphal arches are alluded to on coinage. Left is the reverse of a copper coin issued under the Emperor Trajan (53–117 CE), depicting his temple in the Roman Forum [CM.28-1949].

The city itself was personified as the goddess Roma, seen on [CM.1010-1936], on the reverse of brass sestertius issued under the Emperor Nero (37–68 CE). But like the Greeks, the Romans generally do not not seem to have made realistic portraits of their cities.

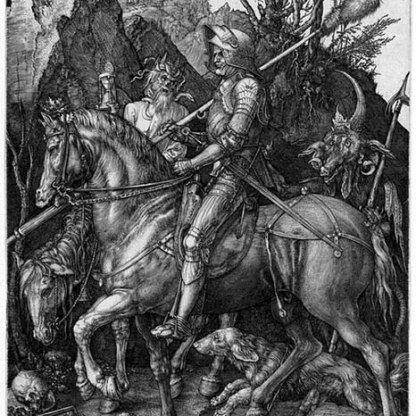

In Christian narrative art, it was sometimes necessary to show cities such as Jerusalem. Sometimes fantastical architecture was invented to suggest the Holy City; at other times elements of known towns were incorporated. The architecture visible on the mountain in the background of Dürer’s The Knight, Death and the Devil, detail left, is a fine example of the kind of distant, imaginary cityscape created by Renaissance artists.

Domenico Veneziano’s Miracle of St Zenobius [1107], with its masterly use of linear perspective, is rare in fifteenth-century painting for depicting a particular street in Florence. The miracle, in which the saint revived a child who had been knocked down by a cart, was said to have taken place on the Borgo degli Albizzi, the street leading up to the church of San Pier Maggiore. The accuracy of Veneziano's depiction here is open to question.

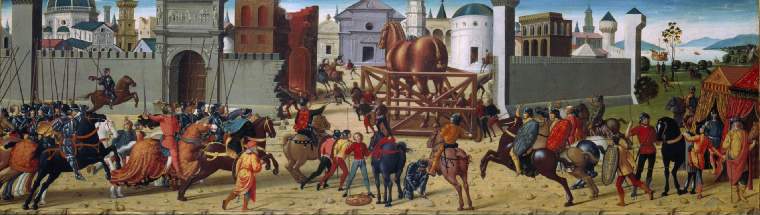

Two late fifteenth-century cassone panels in the Fitzwilliam showing the siege of Troy, above [M.44 & M.45], by the Florentine artist Biagio d'Antonio, combine diverse elements of real Tuscan architecture – the duomo at Florence, the tower at Pisa – with invented buildings to render the doomed city of Homeric epic.

The development of cartography – map-making – had a profound effect upon the depiction of cities in painting. In the late sixteenth century, the Flemish illuminator and draughtsman Georg Hoefnagel provided illustrations for a book by Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg, Civitates orbis terrarum, which contained maps and panoramas of the cities of the world. Running to six volumes, published between 1572 and 1618, it was the most extensive atlas yet produced and, while not entirely accurate, the cityscapes were more detailed than anything that had gone before. There is a copy in the Founder’s Library at the Fitzwilliam.

It was not until the mid-seventeenth century that artists and patrons began to show an interest in the city as a subject in its own right, freed from any particular narrative. A mixture of civic pride and intellectual curiosity led to the flourishing of the cityscape, particularly in the Netherlands. As well as wanting records of the appearance of their own cities, people like the Dutch lawyer Laurens van der Hem commissioned paintings and plans of cities throughout the world, places they would never visit or see at first hand themselves.

Travellers on the Grand Tour were keen to have visual records of their time abroad, and painters found lucrative employment portraying the cities on the tourists' itinerary. In a work from 1797 by the French artist Francois-Xavier Fabre in the Fitzwilliam [PD.16-1984], we see the American traveller Allen Smith contemplating the distant buildings of Florence: a souvenir of his great trip as much as an affirmation of his intellect and good taste.

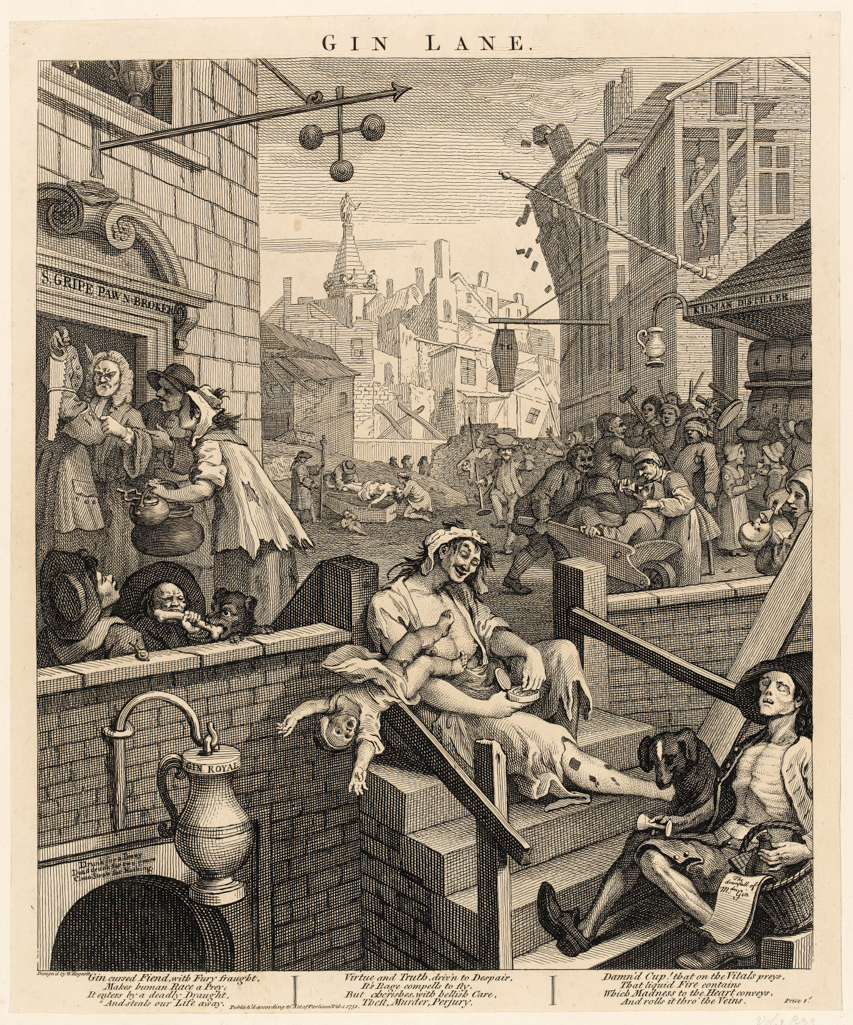

But while the Italian Canaletto [193], and the Dutch artist Gerrit Berckheyde [44], sought to celebrate the beauty of their respective cities, the rapid expansion of London in the eighteenth century led artists like William Hogarth to highlight the harshness of urban living. During the eighteenth century, the population of London rose from 600,000 to nearly one million. By 1750 one-tenth of England’s population lived in the capital city.

Hogarth’s 1751 print, Gin Lane [22.K.3-34], offers an exaggerated but recognisable view of a poorer district of London – the steeple of St George’s church in Bloomsbury is visible in the distance. Over-indulgence in cheap gin was a serious problem among the urban poor at the time, and Hogarth shows the grim consequences: accidents, suicide, grinding poverty, violence.

By the late nineteenth century, factories, railways, traffic and streetlights had radically altered the appearances of cities. More than ever, cities, and those who dwelt in them, became important subjects for artists.

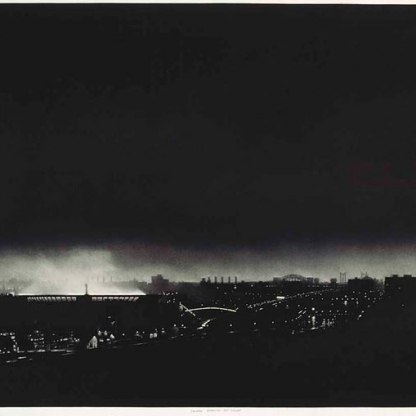

And so it has remained. In the twentieth century, photographers and filmakers have joined painters and printmakers in making cities and urban life central to their art, sometimes celebrating, like Canaletto, sometimes deploring, like Hogarth. A mezzotint in the Fitzwilliam [P.32-1997], Yankee Stadium at Night, by the American artist Craig McPherson (born 1948), a brilliant evocation of the Bronx, New York.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…