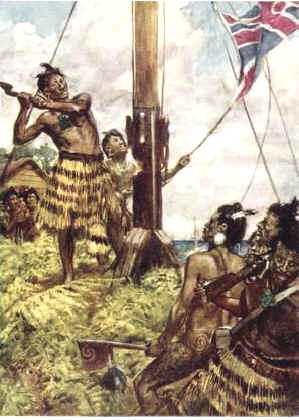

Painting of the felling of the Kororareka flagstaff by Hone Heke, by Arthur David McCormick, 1913, from Wikimedia Commons

The first of the resultant conflicts that is usually described as a war is known as the Flagstaff War, and was begun by the Maori chief Hone Heke at Kororareka (now Russell) in 1845. It should be noted that the war was not occasioned by the presence of Europeans so much as their absence: Hone Heke, who had signed the Treaty of Waitangi, had been dismayed by the subsequent transfer of the new nation's capital from Waitangi to Auckland, meaning a consequent drop in trade and revenue for his people. For this and other reasons, when in 1844 his men entered the town in pursuit of a fugitive, they cut down a flagpole that Hone Heke himself had given the British there, and from which their flag flew. High tensions in the area meant that it became a matter of honour for both sides to either replace or fell the flagstaff, which was defended with increasing resources. On the fourth occasion, in 1845, the Maori attack killed all the defenders and, whether by design or accident is unclear, fired the town, which had been evacuated in the face of their attack; the British then made matters worse by bombarding it from the sea. The British, supported by a rival Maori chief, Tamati Wake Nene, then pursued Hone Heke with artillery and rockets and after a number of inconclusive engagements, including some fought only between Maori, a ceasefire was agreed in January 1846. The flagstaff was not replaced.

H. M. S. North Star bombarding Maori fortifications in 1845, by John Williams, from Wikimedia Commons

Further outbreaks of conflict however followed, in the Hutt Valley in 1846 and the Wanganui Valley later the same year. By now certain factors about warfare between British and Maori were becoming clear to both sides. In the open field, the British, armed with more up-to-date weapons and some light artillery, were more dangerous. The Maori therefore rarely gave them such opportunities and forced the British to seek them out in fortifications known as pa. These wooden stockades were designed with great cunning, their palisades fronted with flax bundles and their defenders accommodated in trenches and bunkers covered with flexible twig roofs also padded with flax. As a result the defenders were almost invulnerable to the British light artillery, whose shells bounced off or failed to explode against the flax, while the Maori themselves were almost hidden from attackers, in rifle pits that gave them perfect firing angles. Such fortifications were, also, relatively quick to assemble, and supplied with evacuation routes that meant that even capture rarely reduced the Maori fighting strength, which the British had then to pursue to the next pa. The Maori however were disadvantaged by long campaigns, as the strength of their men was also needed in agriculture at home, and fighting often had to be abandoned to ensure that the people could be fed. The British could maintain troops in the field without such concerns, and over time could therefore usually force the Maori to negotiations.

Aerial view of pa site (and memorial) at One Tree Hill, Maungakekie, Auckland, from the New Zealand Historical Places Trust

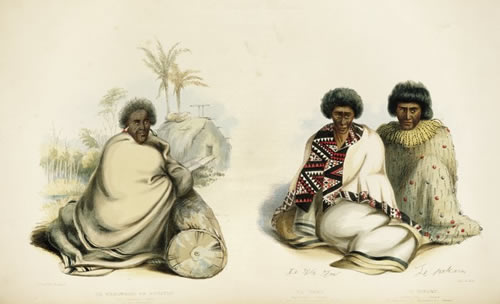

It is important to understand, as stressed at the outset, that neither British nor Maori presented a uniform front during these conflicts. In New Zealand itself there was a division between the operations of the New Zealand Company, frequently illegal stricto sensu but substantial and profitable, and those of the government, some of whose governors felt themselves more bound by the treaty or were more sympathetic to the Maori than others and all of whom lacked resources but commanded a growing body of troops. Further troops, if necessary, had to be got from the Crown territories in New South Wales, however, and the Crown agenda for New Zealand frequently conflicted with both the Company's and the local government's. Meanwhile, some Maori felt themselves bound by the Treaty that they had signed, others felt it was broken by British failures to maintain it and still others had never signed, of whom not all accepted British sovereignty explicitly. Neither were rivalries between Maori peoples entirely quelled by the new rule, often uninterested in Maori-only conflicts. However, as time went on the Maori underwent increasing centralisation, principally in the form of the so-called King Movement, which promoted the Waikato chief Te Wherowhero (a non-signatory and most respected of all the Maori chiefs of his day) as a new king of the Maori to coordinate responses to and negotiate with the British for the whole race in 1858. Although his obedience was far from complete, the colonial government saw this as an affront to British sovereignty and expended much war effort in trying to suppress the movement, unsuccessfully.

Painting of King Potatau Te Wherowhero with two other chiefs by George Angas, 1847; Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, PUBL-0014-44. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any re-use of this image.

The Taranaki province (centre marked) in the context of the North Island of New Zealand

All these factors came into play during the conflicts in the Taranaki area between 1860 and 1869. They arose out of a land sale at Waitara by one Maori chieftain whose superior, Wiremu Kingi, refused his right to sell; Kingi was eventually able to buttress his position with troops sent by the Maori King from Waikato, while British Imperial and government troops were unable to force a decisive action to compel his surrender. The British therefore agreed terms, which neither side respected, and sent forces against the Kingites in Waikato. Their leader, General Duncan Cameron, had his commission with the Imperial forces and disagreed thoroughly with the government's use of troops for what he saw as a land-grab. Despite this, grabbing land was all that his forces accomplished, while the King Movement remained intact further inland from Waikato.

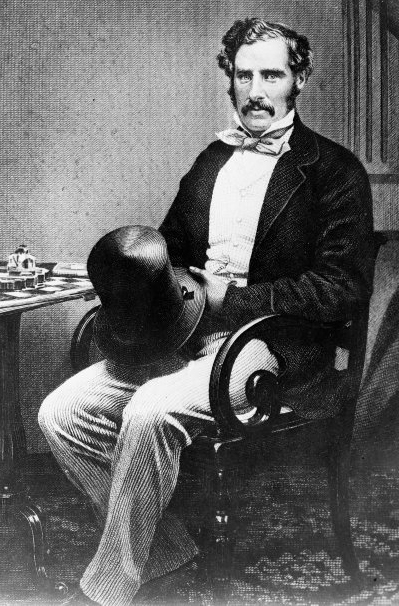

Sir George Grey, probably during his time as Governor General of New Zealand, engraving from photograph by William Wolfe Alais; Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, NON-ATL-0004. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any re-use of this image.

The battle in Taranaki was resumed in a more aggressive style once legislation had been passed in 1863 allowing the government to seize the lands of Maori whom it deemed 'rebels'. Most of Taranaki could be so termed, of course, and although Governor George Grey had, under pressure, annulled the original purchase of land at Waitara, he appears to have waited to announce this until Maori violence against settlers there broke out again in 1864, so as to have a cause de guerre. It was therefore now in the government's, or at least the settlers', interest not to resolve the conflict peacefully, a factor which provoked Cameron's resignation in 1865. Instead, he and subsequent commanders slowly advanced up-country storming fortifications and taking no prisoners.

British troops storming Maori positions under the leadership of Colonel William Messenger, drawn by his son A. H. Messenger

Most of this fighting was done by British troops, but local troops were also involved when Maori troops attacked their areas. Among these troops were the Taranaki Mounted Rifles, and among their number and one of the most highly-decorated of their soldiers was one Antonio Rodriquez de Sardinha.