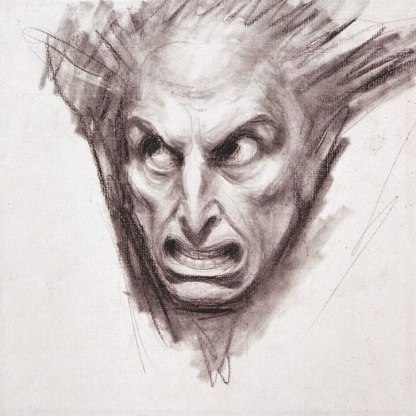

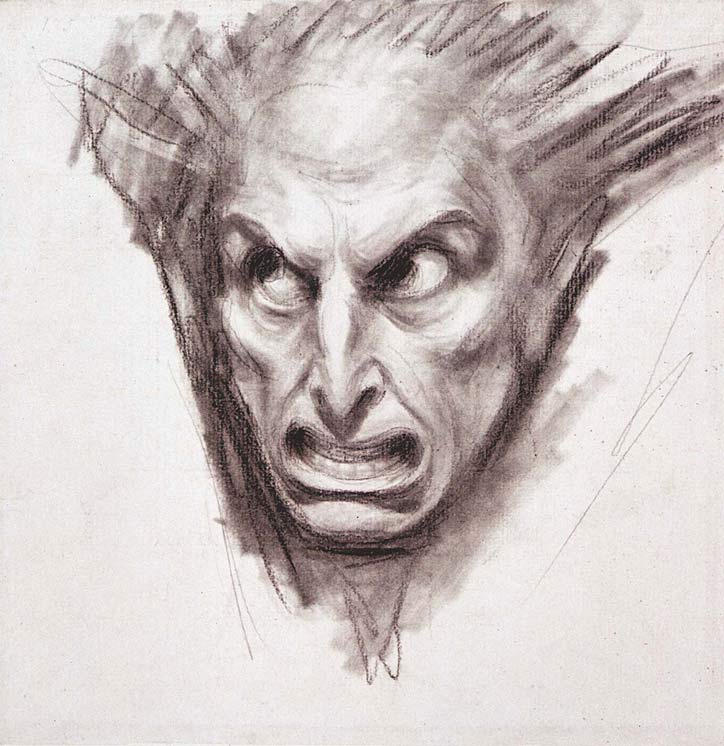

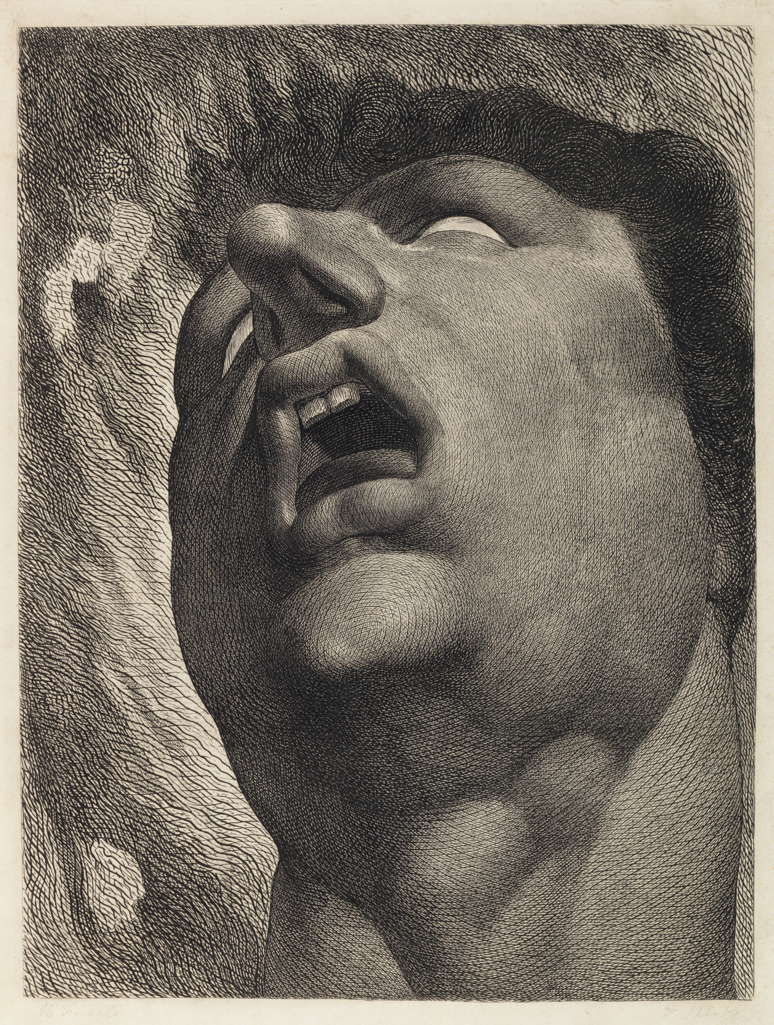

Study for a Fiend's Head

Here they do the ceremonies belonging, and make the circle. It thunders and lightens terribly; then the Spirit riseth.

This stage direction comes from Act 1, Scene 4 of Shakespeare's Henry VI, Part II. The grimacing head in George Romney's drawing belongs to the spirit Asmath, summoned by conjurors in the play at the request of Eleanor, the ambitious duchess of Gloucester. The snarling, clenched teeth and wild, staring eyes vividly suggest the diabolical wickedness of a spirit who, after delivering fearsome prophecies, is dismissed by the black magician Bolingbroke with the words:

Descend to darkness and the burning lake! False fiend, avoid!

The raising of Asmath is a rare example of the supernatural in Shakespeare's history plays, and as such it appealed to Romney. Throughout his career, the artist was widely sought after as a portraitist: above is a fine example of his work in the Fitzwilliam, Mrs Beal Bonnell [PD.131-1992], finished in 1780. But, like his contemporary Thomas Gainsborough, Romney felt that the genre stifled his creativity. In 1787 he complained to a friend:

This cursed portrait painting! How I am shackled by it! I am determined to live frugally, that I may enable myself to cut it short, as soon as I am tolerably independent, and then give my mind up to those delightful regions of the imagination.

In 1786 it must have seemed to Romney that the longed-for opportunity to free himself from 'face-painting' had finally come. For in that year John Boydell, a wealthy London print-seller, conceived a grand scheme to establish a British tradition of historical painting. He commissioned 37 artists to produce a series of canvases based upon episodes from Shakespeare's plays. These were to be displayed in a huge Shakespeare Gallery, a converted bookshop at 52 Pall Mall, London. Boydell hoped to recoup the great cost of this venture by selling prints of the paintings all over Europe.

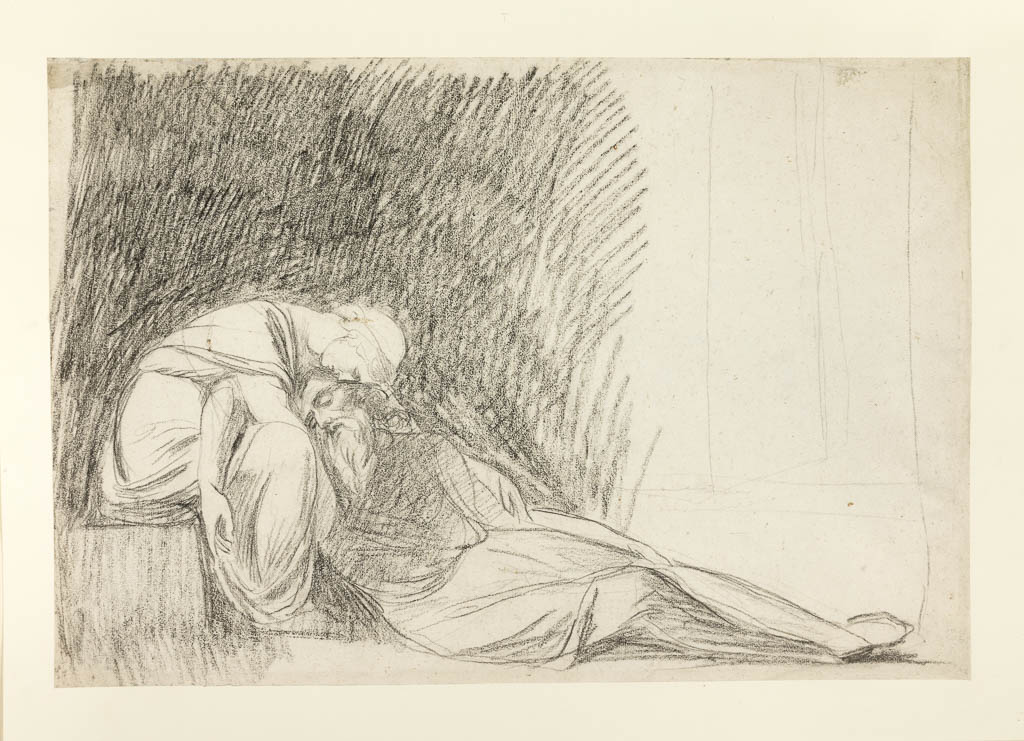

It was the perfect project for Romney, who had long been a devotee of Shakespeare and the English stage. In around 1773, he had made preparatory sketches for a painting of King Lear, above [B.V.7], and in the late 1770s he and a group of friends had formed a small literary society called 'The Unincreasables'. There were eight members, including the celebrated actor John Henderson whom Romney sketched playing the character of Falstaff from Shakespeare's King Henry IV, below [B.V.129].

Romney eventually sent four completed paintings to Boydell's gallery, but they were not well received, and the venture as a whole was a commercial failure. The French Revolution of 1789 and the subsequent wars with France denied Boydell access to the European market where he had hoped to sell his prints.

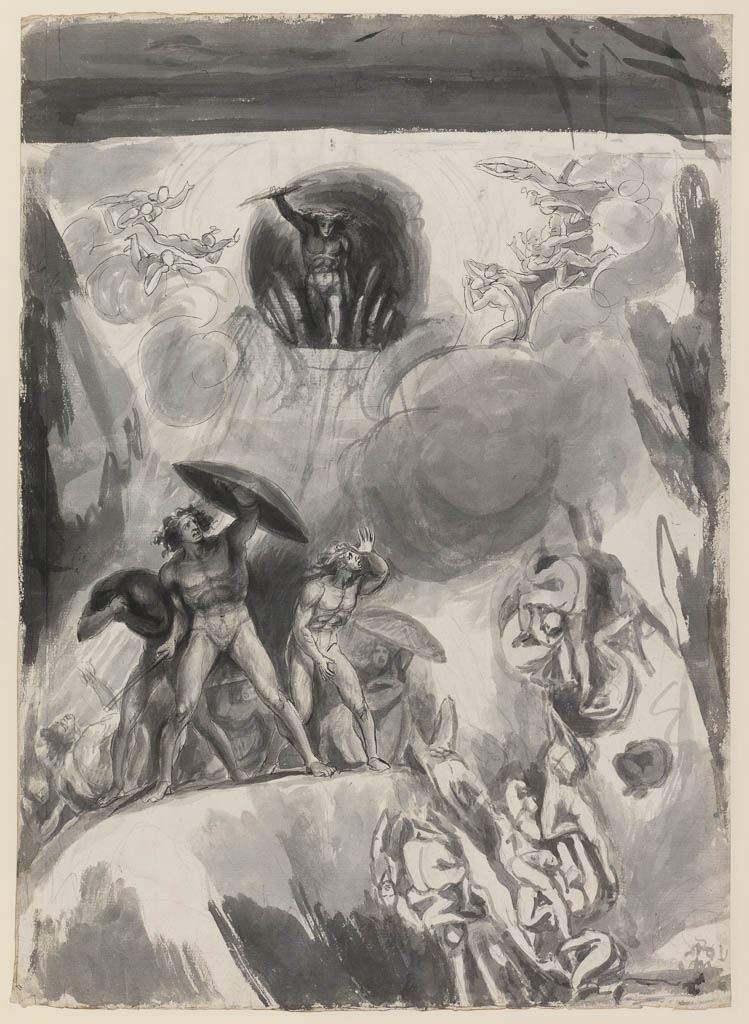

Although the fiend's head never found itself translated into paint, another sketch in the Fitzwilliam, above [B.V.135], suggests the overall composition into which it was intended to fit. Both drawings are good examples of the wilder, more imaginative art to which Romney would have liked to dedicate more of his time.

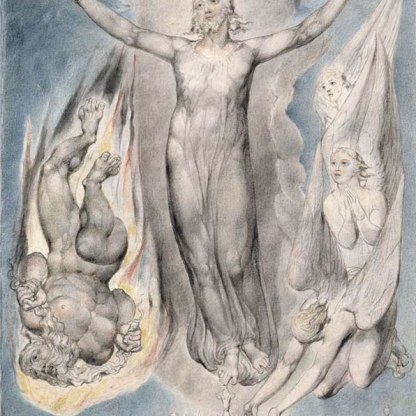

The fiend's head compares with that of Satan in another drawing by Romney in the Fitzwilliam, above [B.V.161], showing 'The Fall of the Rebel Angels', a scene from John Milton's epic poem Paradise Lost, written in 1667.

A print by William Blake in the Fitzwilliam, based upon a painting by Henry Fuseli, above [P.423-1985], depicting a damned soul in Hell, is exactly contemporary with Romney's drawing and makes an interesting comparison.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Unknown

Maker(s)

- Romney, George Draughtsman

Materials used in production

Read more about this recordStories, Contexts and Themes

Other highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…