Christ on the Pinnacle of the Temple

There, on the highest pinnacle, he set

The Son of God, and added thus in scorn,

'Now show thy progeny; if not to stand,

Cast thyself down; safely if son of God ...

John Milton, Paradise Regained, Book 4, ll. 548–50, 553–5, 1671

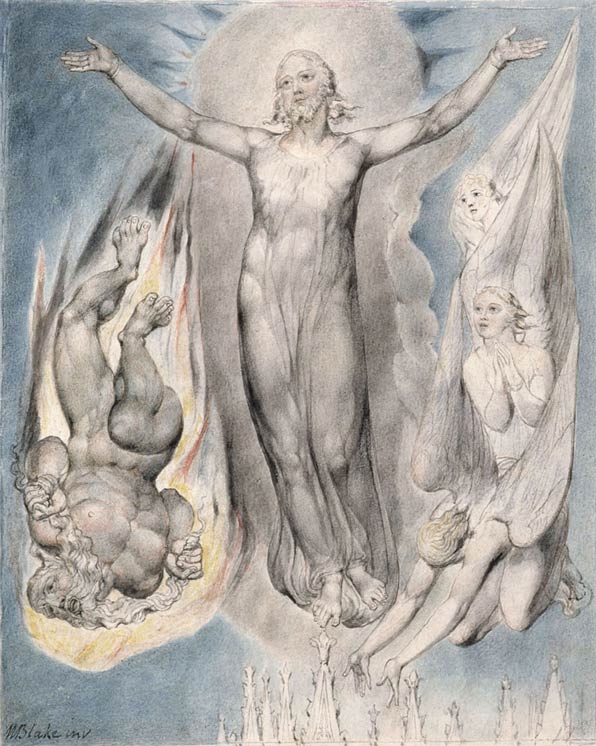

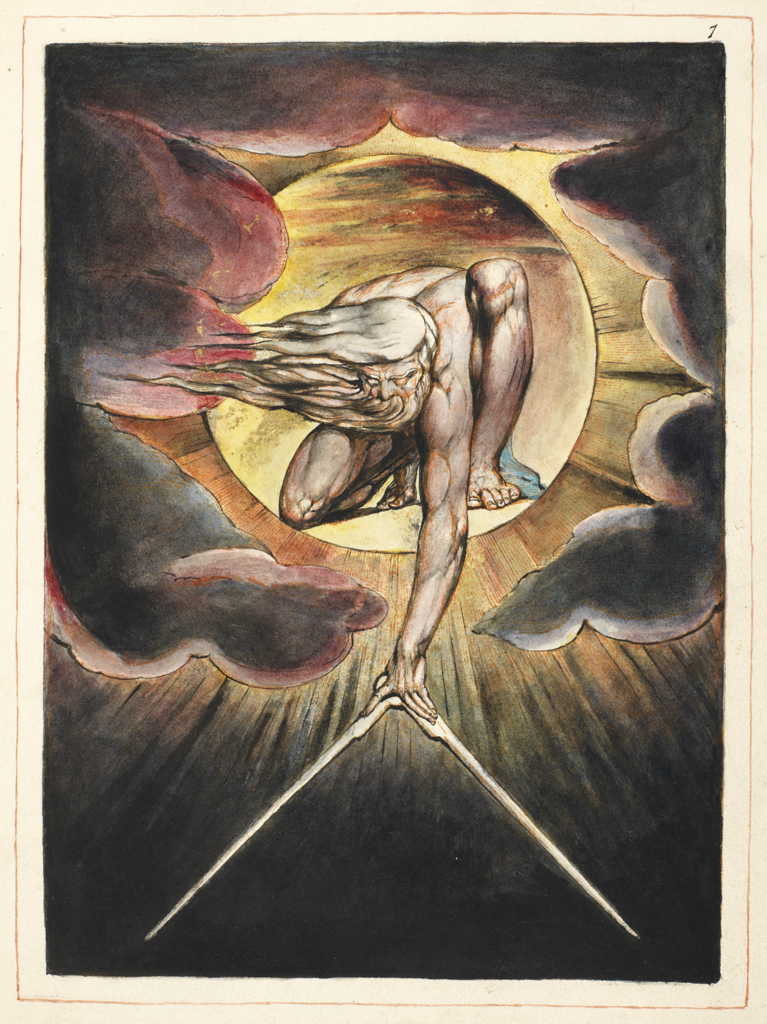

In this dramatic watercolour, William Blake – printmaker, painter, poet and visionary – depicts Christ's final triumph over Satan in the wilderness, a key event in John Milton's poem, Paradise Lost. Having refused to turn stones into bread, having denied himself a lavish banquet, having rejected dominion over earthly kingdoms and having been disturbed by 'ugly dreams', Christ is led to the top of the Temple in Jerusalem. Here Satan challenges him to prove his divinity by either casting himself down or by balancing upon the highest pinnacle. With the words 'Tempt not the Lord, thy God', Christ stands tall, and it is Satan who falls headlong to earth.

This picture is the tenth in a series of twelve watercolours that Blake painted between 1816 and 1818, showing important scenes from Milton's poem. Paradise Regained is a sequel to Paradise Lost, the epic poem in which Milton describes how Adam and Eve are tempted into sin by Satan and cast out of the Garden of Eden. Humanity loses its perfect environment, and is forced to toil and suffer. But redemption is promised by God.

The traditional Christian view has this redemption occur when Christ dies upon the cross and rises again: his self-sacrifice atones for Adam's sin; his Resurrection makes a mockery of Death. Milton and Blake, however, saw the redemption occur earlier in Christ's ministry. The Gospels of Matthew and Luke both relate how, after his baptism, Christ retreated into a desert wilderness for forty days to fast, during which time Satan tempted him with worldly goods and power. The error committed by Adam and Eve, when they were led astray by Satan, was corrected when Christ resisted the same Tempter.

The pinnacles visible at the bottom of this picture, tipped with fleurs de lys, look like the Gothic spires on the great medieval cathedrals of Europe, while Christ's muscular, predominantly grey body resembles a statue rising above the pediment of a Baroque church. This muscularity, this solidity of form, makes his balancing act – on the tip of one toe – appear all the more miraculous.

Christ's posture – arms outstretched, feet close together – is one of triumph, but it also anticipates the position in which he will die upon the cross. In alluding to the Crucifixion at this stage in his series of illustrations, Blake departs from Milton but follows earlier biblical commentators, who identified the pinnacle of the Temple with the cross.

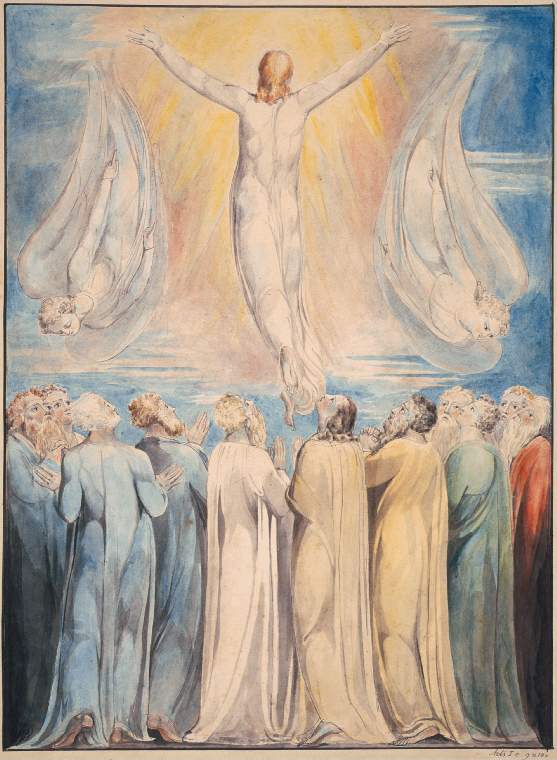

Christ's attitude here also closely resembles that in another watercolour by Blake in the Fitzwilliam, which depicts his Ascension into Heaven [PD.32-1949].

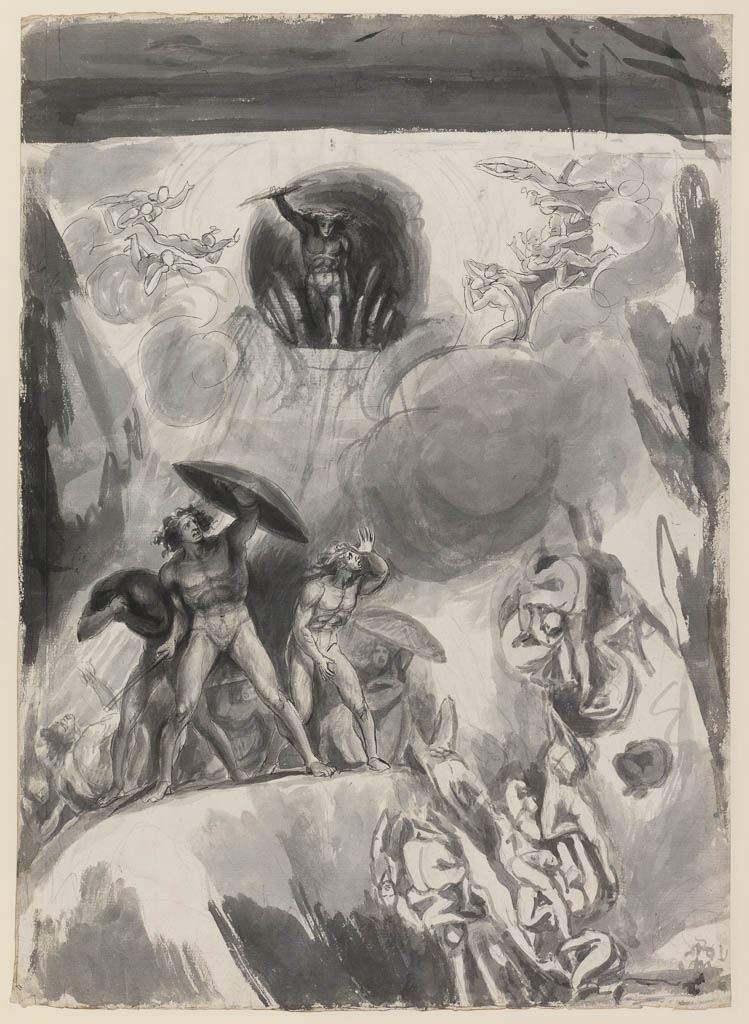

Paradise Lost begins with a magnificent description of the rebel angel Satan falling from heaven. A late eighteenth-century sketch by Blake's contemporary, George Romney, in the Fitzwilliam shows this event [B.V. 161]. In Blake's watercolour, Satan is seen to fall a second time, face first, burning up like a comet as he hurtles to earth, pathetically clinging on to the strands of his long white beard.

His downward plummet is balanced by three angels on the right who effortlessly hover at Christ's side. The lowermost of these stretches his hands towards the pinnacle as if ready to catch Christ, lest by some awful mischance he should lose his balance.

John Milton was to exert a powerful influence over Blake throughout his life. One of the artist's best known images, commonly known as 'The Ancient of Days', which was made in 1794 as the frontispiece to his book Europe: A Prophecy [P.127-1950(19)], is inspired by a passage in Paradise Lost, Book 7, ll. 224–7:

... And in his hand

He took the golden compasses prepared

In God's eternal store, to circumscribe

This universe, and all created things.

In his poem 'Milton' (1804), Blake has his hero return to earth to correct some of the 'errors' of his previous existence. Blake even claimed to have conversed with the spirit of the dead poet. The diarist Henry Crabb Robinson records how once when talking of Milton, Blake told him,

I have seen him as a youth and as an old man with a long flowing beard. He came to me lately as an old man. He said he had committed an error in his Paradise Lost which he wanted me to correct, in a poem or a picture; but I declined. I said I had my own duties to perform.

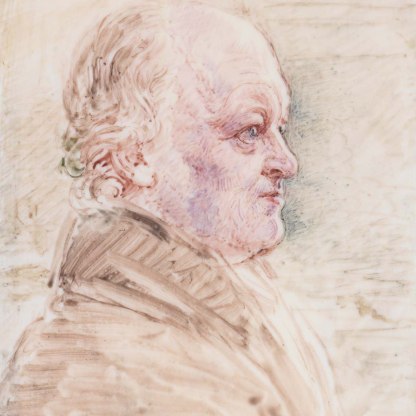

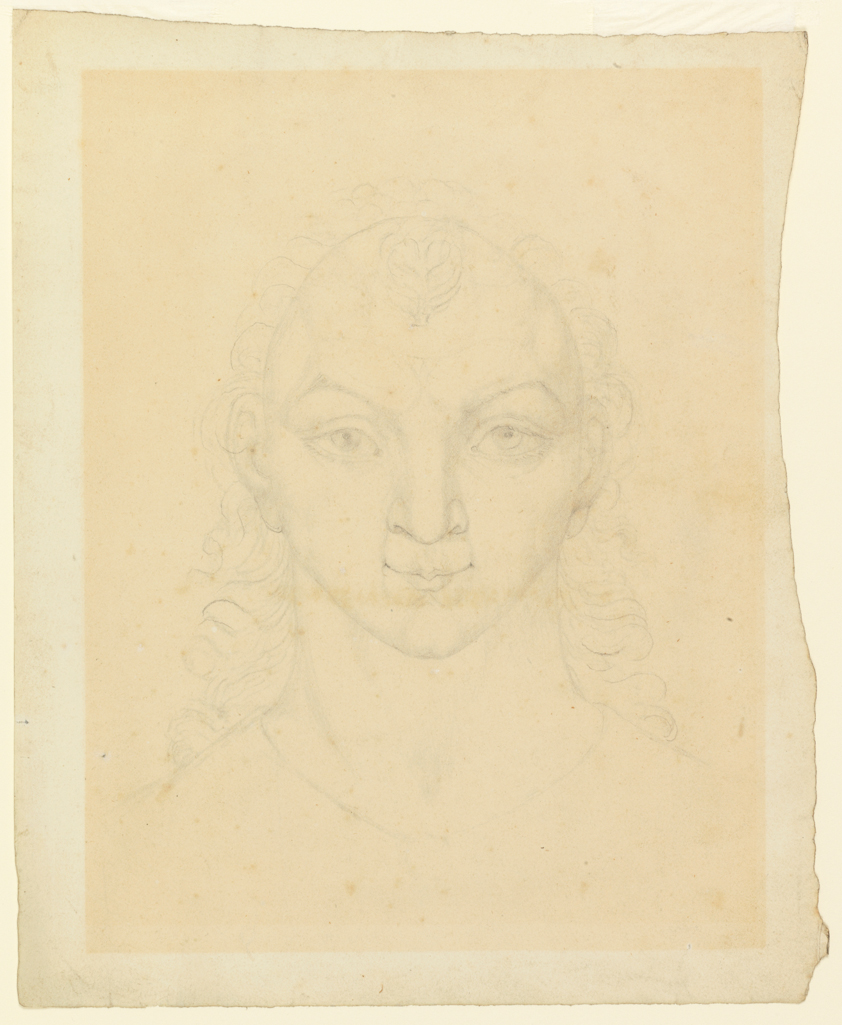

Between 1819 and 1820, with his friend, the artist and amateur astronomer John Varley, Blake drew a series of what he described as 'visionary heads'. One of these he inscribed 'John Milton when Young'. Another, now in the Fitzwilliam [PD.166-1985], is even more mysterious. The artist entitled it 'The Man Who Taught Blake Painting in his Dreams'.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

Bt. from Blake by John Linnell, 1825; Linnell trustees; Linnell sale, Christie's, 15 March 1918 (151), bt. by Messrs. Carfax for T.H. Riches (for 2,100 gns.); Mrs. T.H. Riches

Legal notes

Bequeathed 1935.

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Bequeathed

- Dates: 1950

Dating

One of a series of 12 designs.

Maker(s)

- Blake, William Draughtsman

Note

One of a series of 12 designs.

Materials used in production

Read more about this recordStories, Contexts and Themes

Other highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…