Mirrors

Mirrors in art carry a variety of different meanings and associations.

The oracle of Apollo at Delphi demanded of the ancient Greeks, ‘Know thyself', and mirrors have often been used as symbols of wisdom and self-knowledge. But Apollo also required ‘Nothing in excess', and the mirror can just as easily imply vanity, an unhealthy amount of self-regard. The peril of over-admiring one’s mirror-image is encapsulated in the ancient Greek myth of Narcissus, the beautiful boy who, having fallen in love with his reflection in a pool, pined away and was turned into a flower.

In the ancient world, mirrors were made of highly polished metal, usually copper. Above is an Etruscan example, [GR.10-1972], dating from the fourth century BCE. The back is incised with a scene from Homer’s Odyssey. The Romans are usually credited with developing glass mirrors, but these were not widely used until c. 1500, when convex mirrors were produced in Germany. Venetian glass-makers developed the kind of flat, silvered mirrors we know today.

In ancient art, the mirror is often associated with the world of women and does not necessarily carry any symbolic value, although it was an attribute of the Roman goddess Venus (Greek Aphrodite). On Dexamenos’ fifth-century BCE gem in the Fitzwilliam, the seated woman who looks into a mirror held by a serving-maid is not, one feels, being presented as a narcissist. The artist is simply giving us a privileged insight into the everyday life of women of a certain class in ancient Greece.

In Christian art, the mirror came to represent the eternal purity of the Virgin Mary. As the medieval writer Jacobus de Voragine wrote:

As the sun permeates glass without violating it, so Mary became a mother without losing her virginity ... She is called a mirror because of her representation of things, for as all things are reflected from a mirror, so in the blessed Virgin, as in the mirror of God, ought all to see their impurities and spots, and purify them and correct them: for the proud, beholding her humility see their blemishes, the avaricious see theirs in her poverty, the lovers of pleasures, theirs in her virginity.

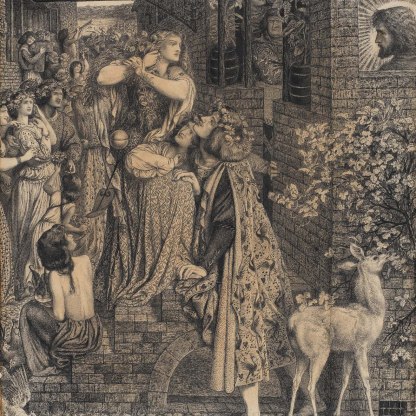

The mirror in art can have other positive meanings. The allegorical figures of Prudence and Truth were often imagined carrying mirrors. Above is An Allegory of Sight [PD.355-1963] from c.1598 by the Dutch artist Hendrik Goltzius, one of a series of drawings about the five senses. A naked woman, perhaps intended to be the goddess Venus or maybe Juno, regards her reflection in a convex hand-mirror. Beside her is an eagle, the bird of the Roman god Jupiter, and the symbol most often used to represent sight in Renaissance art.

Gradually, however, the mirror came to be associated with the negative values suggested by the myth of Narcissus. Vanity and Deception rather than Truth and Prudence were the connotations the mirror carried most often from the Renaissance on. Paulus Moreelse’s painting has been interpreted variously as an allegory of Lasciviousness or Vanity: just as the mirror is dishonest, a carrier of pure illusion, so this girl’s beauty is an illusion, as transitory and shallow as her reflection in the glass.

One way in which an artist can make use of the mirror is to show us something that we would not otherwise be able to see; the reflection of an object or person outside the scope of the painting perhaps. In Moreelse’s painting the mirror provides an alternative view of what we can already see: the girl’s face, this time in profile. Her physical appearance is so important to the painting that we get two views of the same face.

In Alfred Elmore’s Victorian melodrama, On the Brink, above [PD.108-1975], the back wall of the gambling house into which we look is dominated by a tall, narrow gilt mirror. Given its central position opposite the viewer, one might expect it to reflect the window through which we look. It in fact reflects nothing other than the room’s hellish red wallpaper, emphasising the ghastly trap of debt and immoral obligation into which the woman in the foreground has stumbled.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…