The Unicorn

In western art the unicorn, or monoceros – Greek for 'single horn' – is almost always depicted as a small white horse with a single, slender, straight horn projecting from between its eyes. And so it is on the Fitzwilliam’s goblet by Verzelini. The unicorn here is primarily decorative – it has no obvious narrative or symbolic role – but its presence alongside a hound and a stag recall the legend of the unicorn hunt.

The unicorn was notoriously difficult to catch. It could, in fact, only be tamed by a virgin, and this element of the myth made the animal relevant to Christ’s incarnation.

A richly symbolic depiction of the Annunciation – the announcement by the Archangel Gabriel to the Virgin Mary that she will give birth to God’s son. The illumination comes from a Flemish Book of Hours dating from 1526. In a walled garden – symbolic of her virginity – Mary sits intently reading a book, a basket at her side. A white unicorn enters the garden through a gate and rests its horn in her lap. God the Father peeps out of a burning bush behind Mary and, outside the perimeter of the walled garden, Gabriel blows a hunting horn. Two dogs strain at the leash in his hand.

Medieval bestiaries – books which draw theological or spiritual conclusions from observation of the natural world – describe Christ as 'the spritual unicorn' and quote the Song of Songs, 2, 9: 'My Beloved is like the son of the unicorns', and Psalm 92, 10: 'My horn shalt thou exalt like the horn of the unicorn ...

Bishop Ambrose of Milan, the great fourth-century theologian, was one of several early writers to equate the unicorn with Christ. 'Who is this unicorn but God’s only son?' he wrote, 'The only word of God who has been close to God from the beginning.

The unicorn’s proximity to God ‘from the beginning’ is implied in another illumination from a manuscript in the Fitzwilliam[MS 251.f.16]. This illustrates a c.1415 edition of Des Proprietez des Choses, a French translation of an early thiteenth-century encyclopedia written by the English Franciscan monk, Bartholomeus Anglicus.

We see the Garden of Eden before the Fall of Man. God the Father, wearing the three-tiered papal tiara, is apparently joining Adam and Eve in matrimony. He holds their right hands and is about to unite them. Angels and an array of animals watch the ceremony, among them a unicorn who strikes a dignified pose beside the happy couple.

A stream emerges from the ground at God's feet. A dog drinks from it, a white swan glides over its surface and fish can be seen swimming in its clear waters. The unicorn's horn points towards the source, a reference perhaps to the animal's legendary ability to purify water with its horn.

Left is a sixteenth-century print from a series made by the French goldsmith and engraver Jean Duvet for King Henri II of France. A host of thirsty animals line the banks of a stream, unable to drink from it because a serpent has infested the water. In the centre, a unicorn dips his long, straight horn to make it clean again.

The unicorn's purification of water was equivalent, said medieval writers, to Moses cleansing the waters of Marah, the priest consecrating the Eucharist at mass, and Christ's own purification of the world after it had been corrupted by Adam's sin in the Garden of Eden. A fourteenth-century Greek bestiary recorded how the unicorn would even make the sign of the cross over the water before dipping his horn.

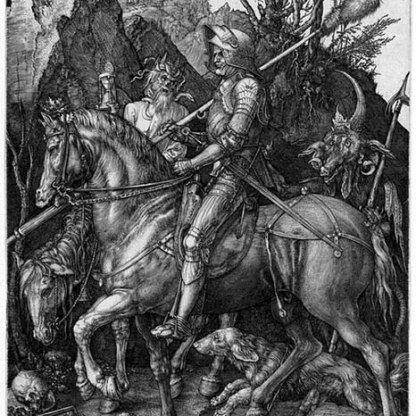

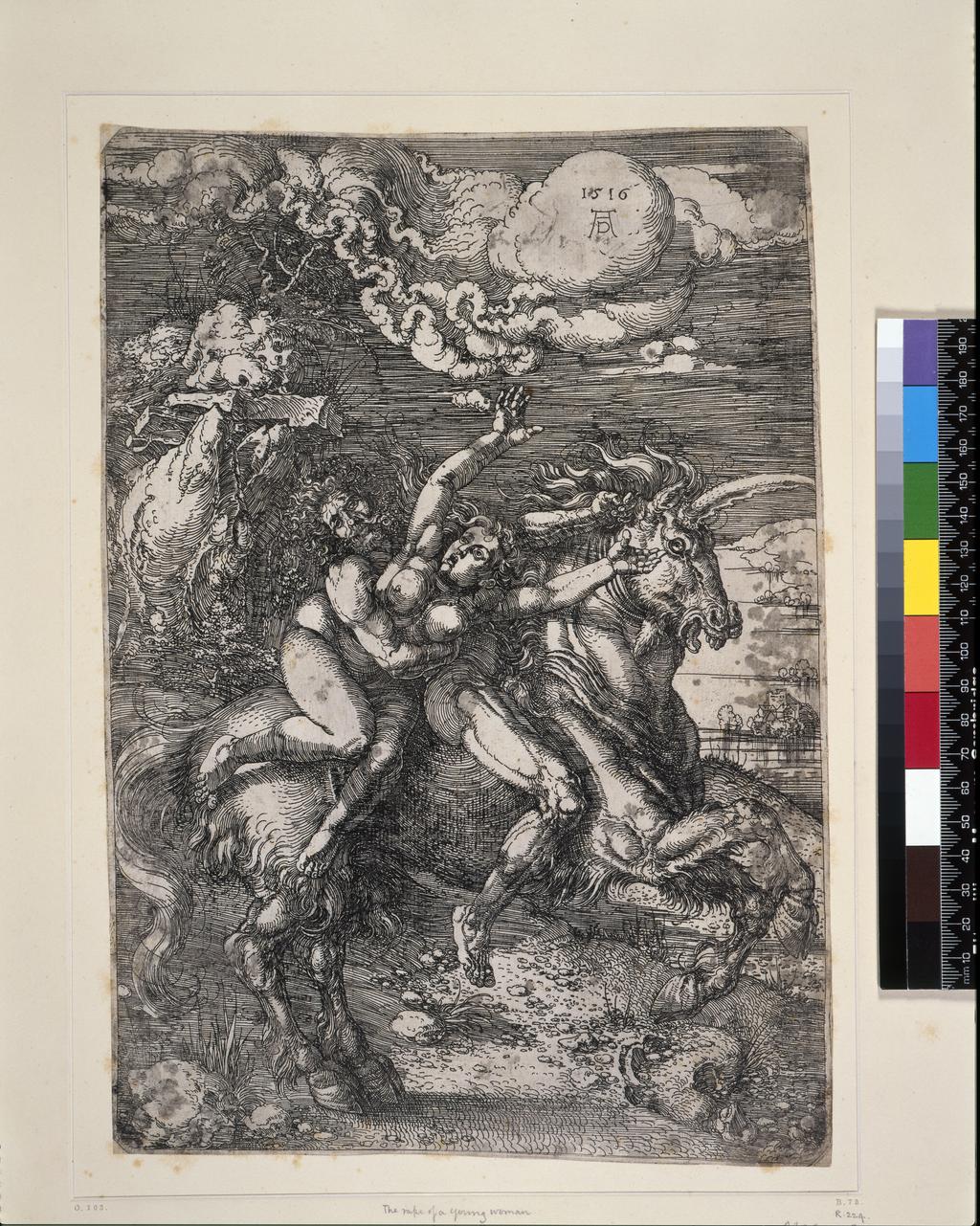

But unicorns in art are not always associated with purity and chastity – there was another tradition that emphasised the ferocity of the animal. In a sixteenth-century print by the German artist Albrecht Dürer, above [35.9.19], a unicorn is the vehicle of violation, carrying the Greek god Hades as he abducts the maiden Persephone. This heavy, shaggy mount with its serrated horn, like a warhorse with a bayonet sticking out from between its eyes, could hardly contrast more sharply with the graceful foal we see in the Garden of Eden above.

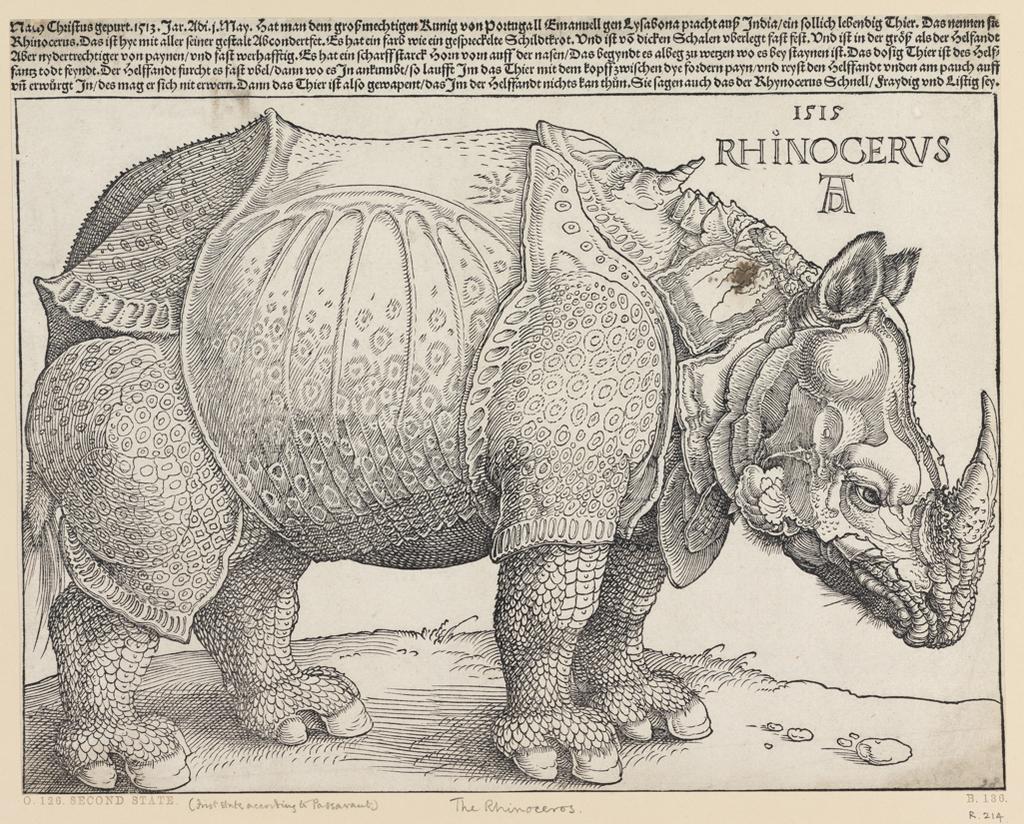

Dürer also famously depicted a real, living one-horned creature that had sometimes been taken for the unicorn of myth – the rhinoceros, above [36.2.43]. When the great Venetian traveller Marco Polo visited Sumatra, the Asiatic rhinoceros was seen for the first time through European eyes. And the eyes were disappointed.

'All in all they are nasty creatures', wrote Marco, 'they always carry their pig-like heads to the ground, like to wallow in mud and are not in the least like unicorns of which our stories speak in Europe. Can an animal of their race feel at ease in the lap of a virgin? I will only say one thing: this creature is entirely different from what we fancied ...'

Dürer, who made his print in 1515 after a drawing by another artist, never himself set eyes on a rhinoceros. The particular animal that he made so famous was a gift to King Manuel I of Portugal from Alfonso Albuquerque, his governor of Portuguese India. Manuel himself offered the exotic beast to Pope Leo X, but the ship it was travelling on sank en route to Rome and all on board were drowned, though the rhinoceros's body was later salvaged, stuffed and sent on to the pope.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…