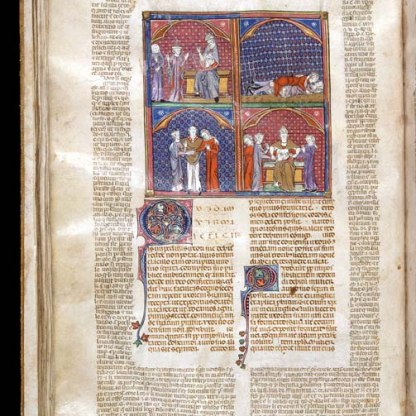

Hermaphtoditus and Salmacis

The painting in the background of Paulus Moreelse's picture shows an episode from the myth of Hermaphroditus and Salmacis. It is told most fully in Ovid's Metamorphoses, Book 4, ll. 290ff.

Hermaphroditus was, as his name suggests, the son of the god Hermes and the goddess Aphrodite, a pedigree that gave him a rare physical beauty. The indolent nymph Salmacis sees him one day when he is travelling and falls instantly in love.

On seeing him, she longed to possess him. But eager though she was, she did not approach him until she had composed herself, inspecting her dress, fixing her expression, and generally making sure of her beauty.

Then she spoke, 'Boy, you really deserve to be thought of as a god. If you are a god, you could be Cupid. If a mortal, then those who bore you are blessed. How happy is your brother. And how truly lucky your sister, if you have one. And the nurse whose breast you sucked.

But far, far more blessed than these is that girl, if there is one, who is engaged to you – if there is any whom you think deserves a wedding torch. If there is such a one, then let my desire be secret. But if there is no one, let me be she! Let us enter the marriage bed together.' With this, the nymph fell silent.

The boy’s face reddened: he did not know what love was. But even blushing suited him. He was the colour of apples hanging on a tree in the sun, or stained ivory, or the moon when it turns red under its brightness, and people ring bronze instruments to try and heal it.

The nymph was ceaselessly demanding if not proper kisses, then at least sisterly ones, and was holding out her hand to his ivory-white neck. But he gave her a choice: 'Will you stop? Or shall I run away and leave all this, and you with it?'

Salmacis grew afraid. 'I leave this place free for you to enjoy as my guest', she said, turned her feet and pretended to leave. But she looked behind her even as she walked away, then lurked hidden in a forest of bushes, down on bended knees.

Hermaphroditus, meanwhile, thinking that he was unobserved strolled around on the deserted grass, dipped the tips of his feet in the lapping water, then went up to his ankles. No more delay: seduced by the coolness of the water, he stripped the soft clothes from his young body. Then was he at his most appealing, and Salmacis burned with desire for his naked form.

The nymph’s eyes were on fire, just as when Phoebus, shining so brightly with his clear orb, is reflected in the image of a mirror that faces it.

She could scarcely bear to wait, scarcely put off her enjoyment any longer. Right then she wanted to embrace him and she could hardly contain herself in her madness.

He leapt into the waters, beating his body with hollow palms and, throwing one arm after another, flashed through the moving water like an ivory statue, or white lilies when someone encases them in clear glass.

'I’ve conquered him, and he is mine', cried the Nymph. Throwing off her clothes, she hurled herself into water and held onto him as he fought, snatched struggling kisses, pushed her arms under him and touched his unwilling breast. She poured herself all over the young man, and finally coiled herself right round him as he struggled against her and tried to slip out of her grasp.

She was like a snake whom an eagle, the king of birds, snatches and holds up on high: the snake hangs its head down and binds the eagle’s feet, and stretches out its tail to entwine its wings.

Or like ivy that weaves around long tree-trunks, or an octopus encircling the victim it has caught under the waves, extending its tentacles in all directions.

Hermaphroditus stood firm, denying the nymph the pleasures she burned for. She pressed him, clung to him with her whole body, and said, 'Fight if you like, but you shall not escape. May the gods command it, that no day will ever take him from me, or me from him.'

Her prayers found gods to answer them, for both their mingled bodies were fused and took on a single appearance. Just as when someone grafts branches into a tree’s bark, he sees them joined as they grow and mature together. So when this couple’s limbs came together in a gripping embrace, they were not two people, but one double form. One could not say it was a woman or a man. It seemed to be neither. It seemed to be both.

When Hermaphroditus saw that the waters into which he had descended as a man had made him into a half-man, and that his limbs had been softened, he stretched out his hand and spoke (though no longer with a male voice):

'Grant this service to your son, my father and mother, both of whose names I bear. Whoever enters this pool as a man, let him leave it as half a man. Let him too grow suddenly weak when he touches its waters.'

Each of his parents was moved to fulfil the words of their bi-form son, and they tainted the source with an unholy drug.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…