Daphne and Apollo

The story of Daphne and Apollo is told in Ovid's Metamorphoses, Book 1, ll. 452–567.

Apollo's first love was Daphne, daughter of the river Peneus. It was not blind chance that caused this, but the wicked anger of Cupid.

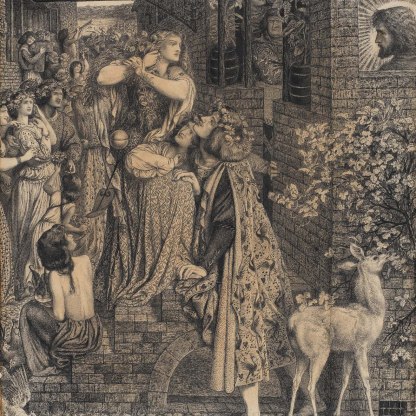

One day the Delian god, Apollo, flushed with pride at his recent killing of the serpent Python, saw Cupid bending his bow, its string drawn tight.

'Saucy lad!' he scoffed, 'What are you doing with those powerful weapons? That kit is suited to my shoulders – I who can wound both beasts and enemies, I who just now laid low with my arrows that swollen Python who was crushing so many acres with his noxious belly. You should be content to use your torch to provoke those love affairs of yours, whatever they are, and not aspire to honours that are mine.'

The son of Venus said to him, 'Phoebus: your bow may pierce all things, but my bow will pierce you. And just as all animals yield to a god, so is your power inferior to mine.'

Saying this Cupid struck the air with beating wings and swiftly landed on the shadowy top of Mount Parnassus. From his quiver he produced two shafts with contrary functions – one banished love, the other created it. The one that caused love was made out of gold and glowed with a sharp point. The one that banished it was blunt and had lead under its reed stem.

The blunt one Cupid fixed in the nymph Daphne, Peneus' daughter, while the sharp one passed through Apollo's bones and pierced his marrow.

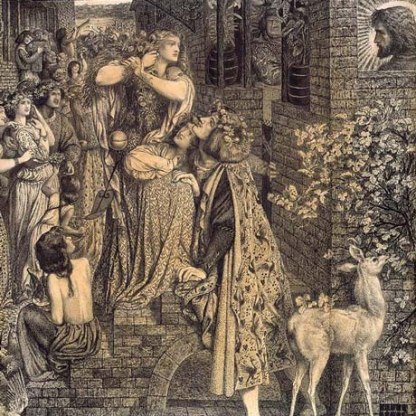

Immediately Apollo was in love while Daphne took flight at the very word, rejoicing instead in woodland dens and the trophies of captured beasts, trying to rival the virgin goddess Diana. A headband held together her unkempt hair. Many men wooed her but she turned them all away. Having no time for men, she roamed the pathless glades. She cared nothing for the god of marriage, or love, or for a wedding.

Often her father said to her, 'My daughter, you owe me a son-in-law,' and as often, 'Child, you owe me grandchildren.' But she rejected marriage torches as if they were a crime. Her beautiful face blushed red and she clung to her father's neck. 'Dearest father', she said, 'allow me to enjoy perpetual virginity. Diana's father allowed her this in the past.'

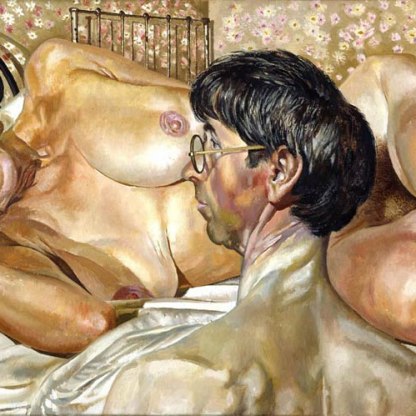

He let you have your way, Daphne. But your beauty rebelled against your prayer. Phoebus was smitten, and upon setting eyes on Daphne he knew he must marry her. As corn stalks are burned after their ears have been harvested, as hedges catch fire from torches dropped by a careless traveller, so was the god in flames. His whole breast burned. And he nourished this fruitless love with hope.

He looked at the nymph's uncombed hair hanging down her neck and wondered, 'What if she wore it up?' He saw her eyes shining with fire: they were like stars. He saw her lips – but just to see was not enough. He praised her fingers and hands, her shoulders, her arms that were naked past the elbow. Whatever was hidden from view, he thought must be even better.

She fled from him faster than the breeze and did not stop to hear the words that he called out: 'Nymph, I beg you, wait! I am not your enemy, nymph. Wait! This is how lambs run from wolves, and deer from lions. Thus do doves flee with trembling wings from eagles. All things flee from their enemies, but the cause of my pursuit is love.

'Darling, oh! Don't fall and let the brambles scar those undeserving legs. Don't let me be the cause of pain to you ... Run slower, I pray. Restrain your flight and I'll follow more slowly. At least ask who it is who so admires you. I am no mountain dwelling bumpkin or shepherd. I'm not one of those yokels who watches herds and flocks. You do not know, rash girl, you do not know who you are running from, and that is why you run. The Delphic land, Claros and Tenedos and the Libyan temple of Patara all serve me! Jupiter is my father! Through me is known what will be, what has been, and what is. Through me, songs harmonise on lyre-strings. My arrow flies straight – but there is one arrow even more sure than mine and it has made a wound in my empty heart. Medicine is my invention and throughout the world I am called Help-Bringer! The powers of herbs are subject to me! But – poor me ! – love cannot be cured by herbs, and the arts which profit the world cannot profit their master!'

He would have said more but Daphne fled from him in a fearful rush. Even then she seemed attractive: the winds laid bare the shape of her body, the breezes she came against met with her clothes and shook them out and a light gust struck her hair and sent it streaming backwards. Her lovely figure was enhanced by running.

But now the youthful god could no longer bear to waste his charming words, and as Love himself urged him, he followed her footsteps with unrestrained strides. It was like when a Gallic hound spots a hare in an empty field: the one uses his feet to seek his prey, the other to seek safety. The hound looks as though he's about to make the grab, and again and again he thinks he has her. He grazes her heels with his outstretched muzzle, while the hare, uncertain whether she is caught or not, tears herself away from the biting jaws, the mouth that's touching her. So it was with the god and the virgin. He was swift with hope, she with fear.

The one who was chasing, however, went faster, assisted by the wings of Love. He gave her no rest, was close on her back, breathing on the hair that was scattered down her neck. Her strength gone, she grew pale. Worn down by the effort of her flight, she spied the waters of Peneus, and said: 'Give me help, father, if your streams possess the power. Change and destroy the beauty for which I was too much admired.'

Her prayer was scarcely finished when a heavy torpor took hold of her limbs. Her soft chest was surrounded by a thin bark. Her hair grew into leaves and her arms into branches. Her foot, that had recently been so swift, was stuck in sluggish roots. A treetop overwhelmed her face. Only her radiant beauty remained.

This tree, too, Phoebus loved. He put his hand on the trunk, and felt the heart still trembling under the new bark. He embraced the branches with his arms as if they were limbs, and planted kisses on the wood. Even the wood tried to escape his kisses.

'Although you cannot be my wife', the god said to her, 'You will certainly be my tree. My hair, my lyre and my quivers shall always wear you, Laurel. You will adorn Latin leaders when a happy voice proclaims a triumph and the Capitol sees long triumphal processions. At Augustus' doorposts you will stand, as faithful guard before his doorway, and see the oak in between. And as my hair is uncut, you too will wear an everlasting crown of leaves.'

Apollo finished. The laurel nodded her new branches.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…