The Flagellants

The ritual of voluntary self-flogging among the laity dates back to the middle of the thirteenth century. After the Black Death tore through Europe, flagellation became so widely and fervently practised that in 1349 Pope Clement VI condemned the practice.

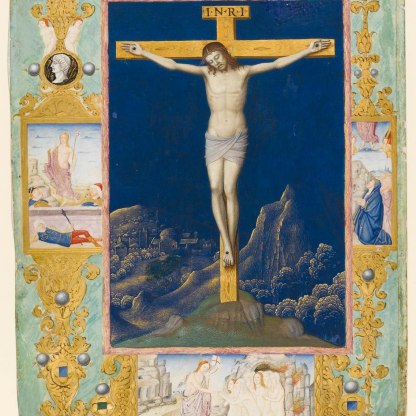

But what was formerly a very public means of appeasing a vengeful God had become, by the fifteenth century, a more private, personal affair. Flagellants whipped themselves in order to more closely share in the sufferings of Christ, who was himself flogged by the Roman soldiers before the Crucifixion. The emphasis was on personal redemption through identification with Christ.

By the fifteenth century in Tuscany, flagellation had become a very popular mode of religious expression. It is recorded that, in the town of Borgo Sansepulcro, all male citizens belonged to a flagellant confraternity.

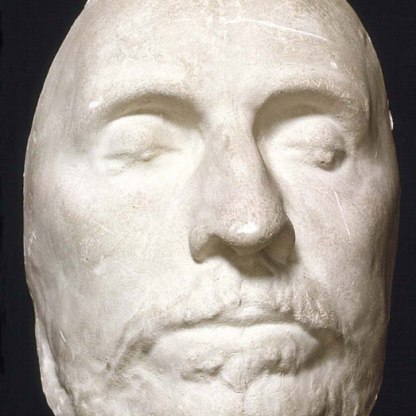

After the death of one of their members, a company would process with the corpse from the dead man's house to their oratory, led by a member carrying the order's crucifix or banner. The brothers then knelt round the bier while the office of the dead was recited. The corpse was buried in the company's tomb in the church, dressed in white robes as a symbol of the resurrection.

Membership of a flagellant confraternity therefore allowed a man to receive a far better-attended and grand funeral than he might otherwise have been able to afford. The soul of the deceased would regularly be remembered and prayed for as part of the order's rites – an important benefit in a society that believed that such privileges shortened one's time in Purgatory.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…