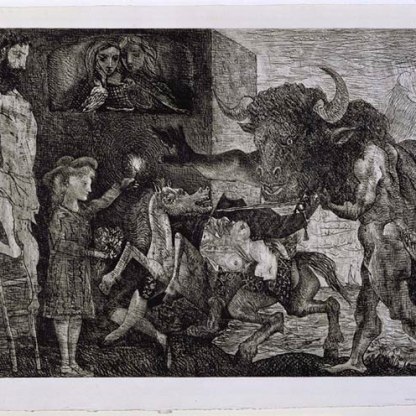

The Death of Hippolytus

Rubens may have come across the story of Hippolytus in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (Book 15, ll. 497–529). But the myth also provides the plot of a tragedy by the great Athenian dramatist Euripides, first produced in 429 BCE.

The hero, a son of Theseus, is falsely accused of attempted rape by his lovestruck stepmother Phaedra, who then kills herself. The widowed Theseus banishes his son from from his kingdom, cursing him in the name of his own father, the sea god Poseidon. As he leaves his home, Hippolytus’ chariot horses are terrifed by a great sea-monster sent by Poseidon, and he is dragged to his death. In Euripides’ play, one of Hippolytus’ attendants comes to tell Theseus of the disaster.

Euripides, Hippolytus 1173–1254

We were near where the shore meets the waves, weeping as we combed out the hides of the horses with scrapers. For a messenger had arrived to announce that Hippolytus was no longer permitted to set foot in this land, that he had been exiled by your decree, Theseus, you pitiable man.

Then Hippolytus himself joined us by the shore and shared our tearful lament, and a great crowd of friends and peers followed him. After a time, though, he stopped crying and said, 'There is no point in despairing about this. My father’s orders must be obeyed. Attendants, prepare the yoke-horses for the chariot. This is no longer my city.'

So then every man applied himself to the job, and faster than you could say it, we fitted out the horses and stood them before our master. He grabbed the reins from the chariot rail, and fixed his feet in the footholds. Then he opened his hands and held them up, and addressed the gods:

'Zeus, may I no longer live if I was born a wicked man. Let my father see that he is wronging me, whether I die or whether I live to see the light.'

With this he took the whip in his hand and laid it on the horses all at once. We servants below the chariot followed our master, keeping close to the bridle, along the road that goes straight to Argos and Epidauros ...

Then there came a noise out of the earth, like Zeus’ thunder, a deep roaring that made you shiver to hear it. The horses lifted their heads and ears towards heaven, and terror descended as we wondered where the sound could come from.

We looked towards the shore, dashed by the salt water, and there we saw a huge, divine wave reaching up to heaven. It blocked my view of the coast of Sciron, and hid the Isthmus and Asclepius’ rock. Swelling up all round, with gallons of bubbling foam from the sea’s blast, it came towards the shore where the four-horse chariot stood. Then, from its enormous billow and surge, this wave produced a monstrous, savage bull ...

To us who watched, this apparition was too much for our eyes to behold. Immediately a dreadful fear assailed the steeds. Our master, expert in the ways of horses, snatched the reins into his hands and dragged them back, like a sailor drags an oar handle, pulling on them with his whole body.

The horses champed down on the fire-forged bits with their jaws, and carried him on by force, refusing to be turned by their captain’s hand or the reins or the strongly welded chariot. And if he held the reins to direct their course towards the softer ground, the bull appeared in front to turn them away, driving the four-horse team insane with fear. But when their crazed minds brought them near the rocks, the bull silently drew near the chariot and accompanied it. Finally it reared up and threw the car, which turned over, striking its wheel rim on a rock.

Everything was mashed together. The wheel rims and the axle pins leapt out of place, and as for poor Hippolytus, he was tangled up in the reins and dragged along, bound up in knotted straps, smashing his dear head on the rocks and tearing his skin, and shrieking horribly: 'Stop! You horses that were reared in my stables, don’t destroy me! Oh, wretched curse of my father! Is there anyone here who is willing to save a noble man?'

There were many of us who were willing to save him, but we were left behind, our feet were too slow. Then he fell free from the binding of the reins which had got severed in some way, I don’t know how, and even then he was still breathing out the little that was left of his life. The horses and the ill-omened monster of a bull vanished, I don’t know where, in the rugged land.

My lord, I am a slave of your own house, but this much I will never be able to do: believe that your son is a wicked man. Not even if the whole race of women were found hanging, or one were to fill all the wood on Mount Ida with writing. For I know that he is good.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…