Mehen Game Board

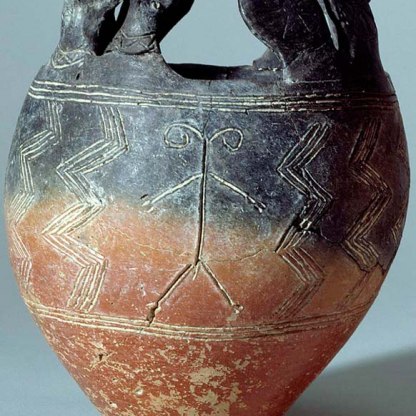

The game of the snake, or Mehen, was a board game played by the ancient Egyptians from at least Dynasties 3-6. Earliest evidence for the game comes from the Predynastic Period (Naqada II phase, 3600 - 3200 BC) and it is the leading contender for the accolade of 'oldest board game in the world'.

The general form of the board is a spiral track based on a coiled snake with the head at the centre and the tail on the edge. The most important evidence for Mehen is within a painting of three board games found by James Quibell in the tomb of Hesy-Ra, a Dynasty 3 high official, c. 2650 BC. Depicted on a wall scene in his tomb is a large Mehen board together with marbles and lion and lioness game pieces. While a board has never been found with its playing pieces, there are several archaeological finds of lion and lioness figurines with small limestone balls and this is generally accepted as typical equipment for the game. The Fitzwilliam Museum has two such lions (see E.4.1927 and E.5.1927) and the Manchester Museum holds a collection of marbles found by Petrie with five lions in a tomb from Dynasty 1.

It is not known how the game was played but certain aspects have been deduced. Evidence for the game has been found almost entirely in funerary contexts and it has been suggested that it represents the final journey of a dead king into the afterlife. The board depicts the serpent god Mehen encircling the sun god Ra, protecting him against enemies during his nightly journey through the underworld. Mehen’s coils therefore also represent a pathway to reach Ra and Mehen was almost certainly a race game in which marbles or other game pieces representing deceased kings were moved from the tail to the head of the snake. It seems likely that lion and lioness pieces were enemies that attacked enroute and were to be repelled. When a piece reached the middle of the board, the king represented by it would have been understood to have been reborn into the afterlife to reside there for eternity, the ancient Egyptian equivalent of heaven or nirvana.

No dice or dice sticks are shown next to the Mehen board in the tomb of Hesy-Ra which leads to an interesting mystery – what mechanism determined how the pieces moved? One theory is that a player would attempt to guess the number of marbles hidden in the other player’s hand – and the outcome dictated how the pieces moved.

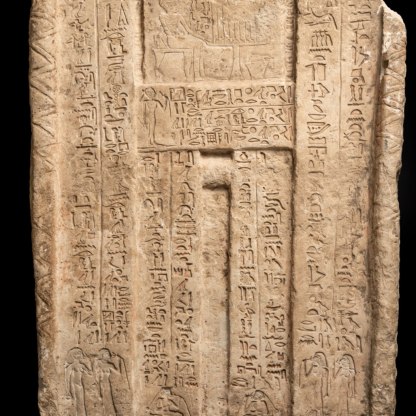

This particular board, held in the Fitzwilliam Museum's collection, is the largest of only eight boards currently known from international collections. Measuring 44cm in diameter, it is made from limestone and was gifted to the Museum in 1943 by Major Robert (John) Gayer-Anderson. The board appears to have been broken into two parts, which have been glued together at an unknown point in the past, and comes with a stand. Detailed examination of the board confirms that the two parts were made independently, as observed by the discrepancies in surface colouration, the banding in the stone and a mismatching join, which is especially visible on the underside. The hatching and size of one portion of the board has clearly been crafted in a poor attempt to correspond with the other, perhaps by Gayer-Anderson for display purposes, although without further technical analyses it is difficult to determine which was the original piece, or when this occurred. The accompanying stand, or single foot, is most likely modern as it appears to have been turned on a lathe.

There are many details on the board worth noting. For example, the snake's body is divided by many grooves forming what most people assume are raised playing spaces. The hood and tail of the snake are hatched and the head features deep recessed eyes (possibly once inlaid with precious stones, which are now missing), and a forked tongue inlaid with red jasper. The larger part also shows the remnant of an appendage on the edge. This is a mysterious feature common to Mehen boards, although it can appear in various forms - other boards, for example, show a goose's head, a large trapezium section or a small turtle's head protrusion.

An important feature of the board is that some of the spaces are hatched. This feature is not known to occur on any other surviving boards. It seems highly likely that these were part of the game, perhaps representing safe spaces or obstacles that needed to be passed.

James Masters, Independent Games Scholar and Melanie Pitkin, Research Associate (Egyptian Antiquities), Fitzwilliam Museum.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

Game board, snake game, circular board with stand, restored

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Bequeathed

- Dates: 1943

Place(s) associated

- Egypt

Other highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…