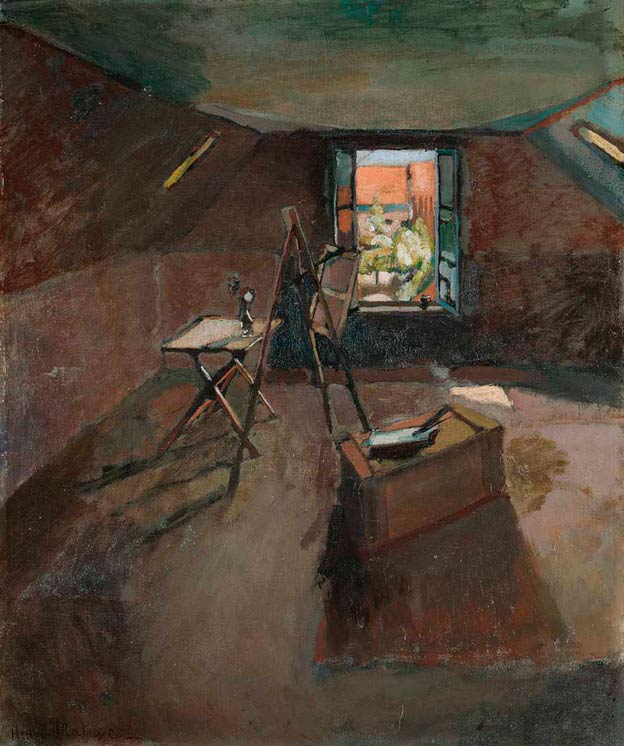

Studio under the Eaves, 1903

We are in great trouble. The various problems, great and small, more great than small, of which ... life has given me a share ... practically decided me to give up painting altogether for a quite different job, insipid but sufficiently lucrative to live on ... Henri Matisse, 15 July 1903

Something of the despair expressed by Matisse in this letter to his old friend, Simon Bussy, found its way on to this canvas, painted at around the same time. It is one of relatively few works that the artist completed during what has been referred to as his ‘dark period'. The adjective applies to his mood as much as to his palette. The studio depicted here was on the top floor of 24 Rue Fagard in Bohain, the small, northern town in which Matisse had grown up and to which in 1903 he had returned, the exhausted and depressed head of a young family.

At the time Matisse was having to provide not only for an ailing wife and three children, but also for his parents-in-law. France had been rocked by a financial scandal at the centre of which stood his wife’s father and mother, Armand and Catherine Parayre. Innocent of any wrong-doing themselves, the couple had been employed by one Thérèse Humbert, who, by a remarkably bold series of confidence tricks and outright lies, had managed to relieve hundreds of people of their life savings. Humbert had been exposed as a fraud in 1902 and had gone into hiding.

Like everyone else, the Parayres suffered financially from the scam, but the authorities and the public found it hard to believe that they could have been so blind to their employer’s villainy. The hat-shop belonging to Matisse’s wife and the artist's own studio were raided and searched by police. When the Humberts were eventually found hiding in Madrid, Armand Parayre was arrested and the pressure finally got to Matisse himself. In the winter of 1902, suffering from insomnia and nervous exhaustion, he was advised by doctors to rest entirely for two months.

He returned to his parents’ home in Bohain, but the welcome there was hardly warm. His father, who had wanted his son to become a lawyer, could not hide his disappointment. His fellow townsmen were unimpressed by his untraditional approach to painting and he was scarcely able to make ends meet as an artist. It was in this context that Matisse painted the attic in which he found refuge.

The makeshift, spartan look of this studio under the eaves suggests the painter’s financial straits. His palette rests upon a simple wooden crate. His easel is set up before a folding table, on which stands a single vase containing two dahlias. Matisse’s fellow artist Jean Puy, with whom he had shared a studio in Paris before returning to Bohain, recalled how in 1902 his colleague had been 'profoundly moved by the sight of some flowers withering in a vase: their faded colours, their melancholy grace touched something in him'. Like Dutch flower painters of the seventeenthth century, perhaps Matisse saw the plucked flower as a symbol of the vanity of human life.

The two skylights at either side of attic's slanting roof do little to illuminate the interior. Even the daylight that enters the open window serves only to intensify the darkness of the foreground by casting a long, dark shadow from the chest on which the artist’s palette rests towards the viewer. But it is this source of light to which all the elements of the painting – and our gaze – are directed. The lines formed by the angles of the room, the shadows cast by the table and the easel: all point towards the window. The canvas leans from the easel as though thirsting for the light, like a sunflower.

Later in 1903, the Parayres’ names were cleared, the Humberts were imprisoned, and Matisse and his family returned to Paris. From there they moved to St Tropez in the south. In the years that followed, Matisse would become one of the best known and admired painters in France, his output distinguished by his remarkable use of colour. The window in this gloomy attic looks out onto a more visually vibrant world, towards a brighter future.

Themes and periods

Data from our collections database

Bernheim-Jeune, Paris(BJ46 OP17); Vente Peau de l' Ours, 2 March 1914, no. 37

Legal notes

Bequeathed by A.J. Hugh Smith through the National Art-Collections Fund, 1964

Acquisition and important dates

- Method of acquisition: Bequeathed

- Dates: 1964

Dating

- 1900s

- Production date: circa AD 1903 : D. Cooper, Feb. 1965, dated it about 1900; according to Barr (loc. cit. p. 50), painted at Bohain-en-Vermandois, early in 1903.

Maker(s)

- Matisse, Henri Painter

Materials used in production

Read more about this recordOther highlight objects you might like

Suggested Curating Cambridge products

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…