Iconoclasm

Thou shalt not make unto thyself any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth; Thou shalt not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them: for I the Lord God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children unto the third and fourth generation of them that hate me; And showing mercy unto thousands of them that love me, and keep my commandments

Exodus, 20, 4–6

The Old Testament seems unequivocal in its condemnation of imagery of any kind, particularly religious imagery. And yet figurative art, often with a biblical theme, has been produced by Christians for Christians since at least the third century CE. As the visitor to the Fitzwilliam can hardly fail to notice, the events of the Old Testament, the life of Christ and the lives of the saints have inspired, and continue to inspire, artists in all media. Figurative art in the form of sculpture is built into the fabric of many churches. When figures are depicted upon an altarpiece they form a focus of prayer. Private devotions are still aided by the contemplation of religious pictures.

This apparent contravention of the Second Commandment has attracted continuous attention from theologians, worshippers and art historians. But the debate about the validity of Christian images first became a crisis in the Byzantine empire in the eighth century, during what is known as the iconoclastic controversy.

Today the word 'icon' is usually used to mean a person or emblem representative of an age, movement or place: Marilyn Monroe, for instance, or Che Guevara. More recently it has come to mean a graphic on a computer screen. But the Greek word from which it derives means ‘likeness', and in art history the word icon refers to Christian images of the saints, Christ or the Virgin. It is most often used to refer to painted images on wooden panels, but the word can refer to work in any medium. The Fitzwilliam ivory is an icon of Christ.

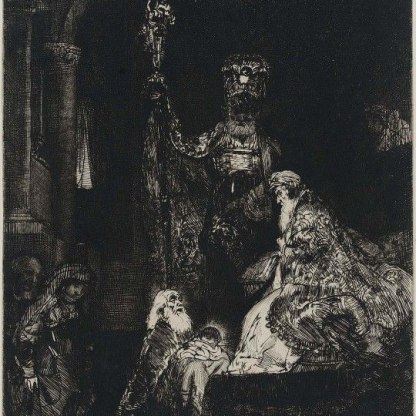

Iconoclasm means the deliberate destruction of such images. And between 726 and 843 CE, an impassioned debate was conducted between iconoclasts (those who would destroy all religious images) and iconodules (those who revered them). The legend of Theodosia, a nun who suffered martyrdom whilst defending an icon of Christ, suggests the strength of feeling on both sides.

Iconoclasts may have been influenced by the rise of Islam: the followers of Allah were strict in their rejection of figurative art in a religious context. To direct prayer towards an image, to bow before it or to kiss it, was to return to the idolatrous practices of pagan Rome. To circumscribe Christ in paint was to belittle his divine nature. For the iconoclasts, the cross alone was sufficient as a visual symbol of the Christian message.

The iconodules argued that since in Christ, God had become man, his representation in paint was justified. They distinguished between the reverence given to an icon, and the worship directed towards God. They were not committing idolatry, they said, because they were worshipping the prototype upon whom the likeness was based, and not the material of the icon itself.

Finally, a Church Council in Constantinople in 843 ruled in favour of the iconodules. Icons were permitted once more as part of daily worship – a decision that is still commemorated on a feast day in the Orthodox Church known as 'The Triumph of Orthodoxy'.

Very little imagery survives from the period before iconoclasm. But we can sense a continuity when we compare the post-iconoclastic Fitzwilliam ivory with a gold coin (CM.2063-1950) of Justinian II (669–711) that predates the controversy . Here we see the same bust of Christ holding a book and blessing the viewer. He has the same distinctive tuft of hair below his centre parting. He is backed by the same three arms of the cross.

The Emperor Michael III (836–67), who with his mother Theodosia presided over the reintroduction of icons, reintroduced this type of Christ onto Byzantine coinage during his reign. The emperor now sat once more in his palace beneath a large picture of an enthroned Christ in Majesty, an echo of which we may trace in the Fitzwilliam ivory.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…