Tea

The first advertisement for tea in Britain was printed in The Gazette, a London weekly, in September 1658:

That Excellent, and by all Physitians approved, China Drink, called by the Chineans, Tcha, by other Nations Tay, alias Tee, is sold at the Sultaness-head, a Cophee-house, in Sweetings Rents by the Royal Exchange, London.

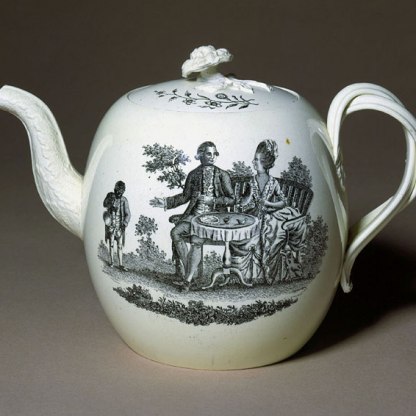

Tea, which has been drunk in China for about 5,000 years, was introduced into Europe by traders from the Dutch East India Company in the early 1600s. The drink became popular among the upper echelons of British society when Charles II's wife, Catherine of Braganza, brought a taste for the brew from Portugal. The exoticism and expense of tea added to its appeal, and the Chinese porcelain vessels associated with tea making and drinking became in themselves highly desirable items. While the rest of Europe fell under the spell of coffee and chocolate, the taste buds of England were seduced by tea.

In William Hogarth's painting from the 1730s, A Musical Party, in the Fitzwilliam [647], members of the Mathias family are shown playing musical instruments and drinking tea, a sign of their status and sophistication.

As the advertisement quoted above suggests, the drink was also credited with medicinal value. The water supply in England at the time was not clean and the makers of beer - the safe, staple beverage for the majority of the population - felt their livelihood threatened by the new hot and healthy drink. The government responded to pressure from this powerful lobby, and 1698 saw the introduction of the first specific tea tax, which was doubled in 1704 and increased again eight years later. This made the drink prohibitively expensive for all but the richest. In 1706 a leading dealer was selling green tea for the modern equivalent of £160 for 100g. And yet by 1721 over 1 million lb (over 450,000 kg) of tea was being imported annually into Britain. In 1717 Thomas Twining opened the first shop in England, possibly in Europe, solely devoted to the selling of dry tea.

The woman of the house would traditionally hold the key to the boxes in which this valuable commodity was kept. A magnificent silver set of two tea caddies and a sugar box, owned by the founder of the Fitzwilliam Museum and bearing his coat of arms [M.7(a,b,c)-1965], suggests the esteem in which the leaves were held. Stored themselves in a velvet-lined mahogany box, these luxurious containers are marked on their lids: B for Bohea – a popular type of black China tea; S for Sugar and G for Green tea.

At first, tea was traditionally a female drink. While men would gather to smoke and unwind in London's rowdy coffee houses, women would meet over tea at home. But as the coffee houses declined in the eighteenth century, this divide broke down. The taking of tea became a family tradition and provided an occasion upon which men and women could get to know each other socially. It was also part of the experience of the eighteenth-century pleasure gardens in London, like those at Vauxhall or Ranelagh where, in 1764, Leopold Mozart noted that 'On entering everyone pays 2s. 6d. For this he may have as much bread and butter as he can eat and as much tea or coffee as he can drink.'

By this time tea, though still expensive, was available across a broader section of society. The massive taxes levied upon it had given rise to tea smuggling and there was a significant black market. Unscrupulous sellers would adulterate the leaves with fillers like sheep dung. When, towards the end of the century, poor grain harvests led to a sharp increase in the price of beer, the taxes were revised and tea became the favoured beverage of the common man. Twenty-four million lb (nearly 11 million kg) of tea were now imported to England annually.

Throughout the nineteenth century, the popularity of the drink soared as it became even cheaper and more readily available. From 1848, plants taken from China were grown in Assam in north-east India, which was then under British control. New ships developed in America, the 'tea clippers', meant that journeys that might previously have taken a year could now be accomplished in about 100 days. And with the development of steam ships and the construction of the Suez canal between 1859 and 1869, the transportation of tea from the East became easier than ever.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…