The Adoration of the Magi

The earliest representations of this popular subject are found painted in the catacombs of Rome and carved on marble sarcophagi from between the second and fourth centuries CE. The basic composition, in which the Magi kneel before an enthroned Virgin and Child, is derived from Roman imperial images of defeated barbarians offering homage to their Roman victors. Left is a coin of the Emperor Trajan which depicts a king of Dacia doing obeisance before the Imperial throne.

The symbolic values of the gifts brought by the Magi – gold, frankincense and myrrh – were specified at the end of the second century CE, by St Irenaeus. Gold, he said, stood for tribute, frankincense for sacrifice, and myrrh for burial. The gifts therefore referred to the kingship, the divinity and the humanity of Christ.

In the middle ages, the Magi were interpreted as personifications of the three parts of the known world. Caspar is usually an older, white European. Balthasar is a middle-aged Asian. Melchior, particularly in northern European art, is often shown as a younger, usually beardless African.

In the Renaissance the royalty of the Magi is stressed, and they are usually lavishly dressed and accompanied by a retinue. In a painting in the Fitzwilliam [1784], by the Netherlandish artist Joos Van Cleve, the older Magus, kneeling before Christ and kissing his hand, is wrapped in a particularly impressive, gold embroidered cloak.

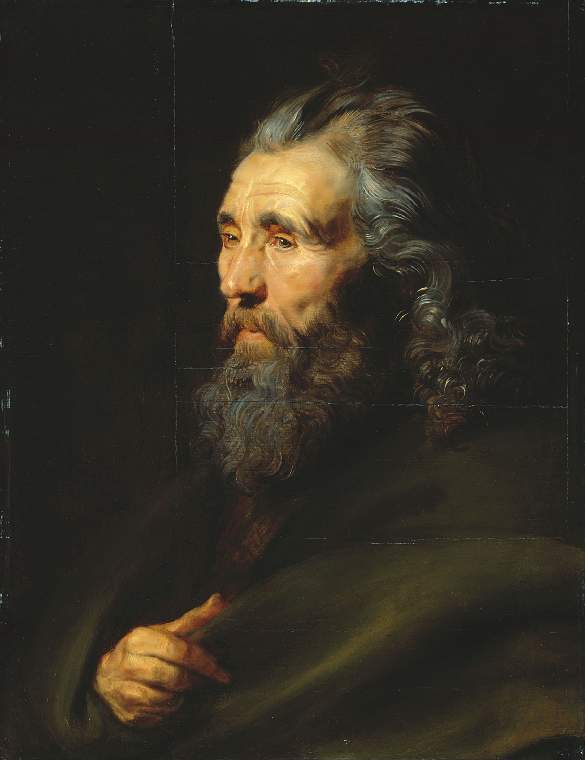

The subject remained popular, particularly in the seventeenth century. Two fine male portraits by Peter Paul Rubens in the Fitzwilliam, one of which is illustrated [PD.13-1980], are studies for his treatment of the subject.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…