The Lion of Nemea

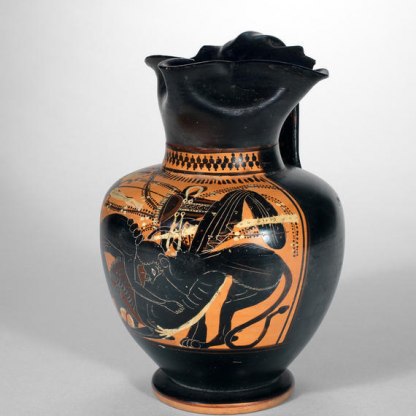

From the seventh century BCE in Greece, Herakles fight with the Nemean Lion was the most popular of his many exploits to be shown in art. The most complete ancient literary account of the fight that survives is that of Theocritus, a Greek poet writing in the third century BCE. Herakles himself is describing the adventure.

I will tell you every detail of how it happened, since you are keen to hear it – except for where the monster came from. For in all the towns of Argos there is no one who could tell you that for sure. We can only suppose that one of the immortals sent it as an affliction on the children of Phoroneus, in wrath at some neglected sacrifice. For the savage lion was wasting all the meadowland, rushing through it like a river – especially the land of the people of Bembina. As neighbours in his land, they were made to suffer intolerably.

This, then, was the first trial Eurystheus assigned me to complete – he ordered me to kill this dreadful beast. So I took my supple bow and my arrow-filled quiver, and in the other hand I gripped my sturdy club, which is made from the whole length of a shady wild olive tree with all its bark still on. I personally found this under holy Helicon and pulled up in its entirety, with all its mass of roots.

Then, when I reached the region where the lion was, I took my bow. I drew the twisted string down, fastening it to the tip, and loading it with a pain-bearing arrow, I immediately set off. I looked around me, turning my eyes everywhere in search of the murderous beast, hoping to catch sight of him before he saw me.

It was midday, and nowhere could I see his tracks or make out his roaring. There was nobody to be seen there at work, no one driving oxen or sowing furrows whom I could stop and ask – pale fear was keeping all the people inside their homes. However, I refused to stop searching the leafy hillside until I should see the lion and put my strength to the test.

Sure enough, towards evening he came back to his cave in the rocks, glutted with flesh and blood. His dirty mane, his face and chest were all splashed with gore, and his tongue slobbered round his jaw. I immediately hid under the cover of some bushes, and as he approached I shot at his left flank.

Uselessly, as it turned out. The barbed weapon couldn't pierce his skin, but was knocked back onto the fresh green grass. Caught by surprise, he swiftly looked up from the ground. Raising his blood-drenched head, he cast his eyes around him, scanning the whole area, his mouth gaping to reveal his gluttonous teeth.

I fired another missile from the bowstring, alarmed that the first one had left my hand to no effect. This struck him in the middle of the chest, right where the lungs are positioned. But the arrow that can bring so much pain did not even break his skin. It fell wasted at his feet.

I was frantically annoyed, and was all set to draw a third time, when the ravening beast turned his eyes and saw me. He whipped his great tail around on his hind legs and straightaway was mad for a fight. He was brimming with wrath. His fiery mane shook with rage. His back arched like a bow, as he drew every part of himself under his flanks and waist.

It was just like when a man who makes carts, a clever skilful man, bends the fresh branches of a wild fig tree. The fig branch with its light bark escapes from beneath his hand and springs away with one quick motion. So did the dreadful lion from far off suddenly spring upon me, panting with desperation to rip my flesh.

I, holding out my arrows and cloak with one hand, raised my hard club above my head and rammed it down onto his skull. The rough wild olive club smashed in two on the shaggy head of that unconquerable beast. Before he reached me, he fell down onto the ground, and stood tottering, his neck bent. Darkness had come over both his eyes. His brain was violently shaken inside his skull.

When I saw that he was giddy with pain, before he could turn round and recover himself, I struck. I cast my bow and thickly embroidered quiver to the ground, and I drove my club down onto the nape of his unwounded neck. Then I thrust my arms together closely around him and squeezed hard, getting behind him to avoid him tearing my skin with his talons, and standing firmly on his hind feet with my heels. I trod them into the ground to protect my sides from his legs and squeezed him hard, until I could raise him up straight by his forelegs. I stretched him out and suffocated him, and mighty Hades took his spirit.

After that, I was debating how I could flay the shaggy-necked skin from the beast's corpse. It was an extremely tricky problem, since the hide could not be cut when I tried with wood or stone or iron. Then one of the immortals put the idea into my mind to take off the skin with the lion's own talons. With them I swiftly skinned it, and put it around my body as a protection from the wounds of warlike hunting. This, my dear friend, was how it happened – the destruction of the Nemean Lion, that had brought so much suffering to flocks and people.

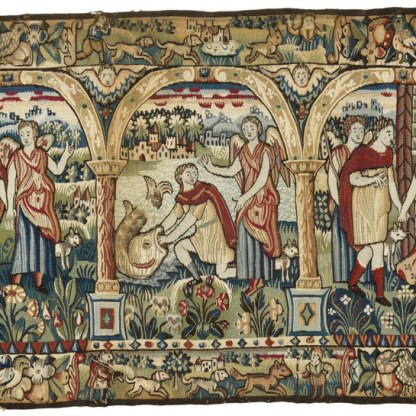

After the mighty battle, Zeus, to commemorate the victory of his son, set up the lion in the sky as the constellation Leo, seen left in a medieval book of Astronomy in the Fitzwilliam [MS.260.f.20r]. It thus became the ultimate trophy and symbol of victory.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…