Feathered Caps and Lutes

Seventeenth-century Dutch literature makes full play of allegory, metaphor, pun and double entendre. Words rarely represent just one thing. In the same way, objects in Dutch genre paintings or prints often have a significance beyond their literal meaning.

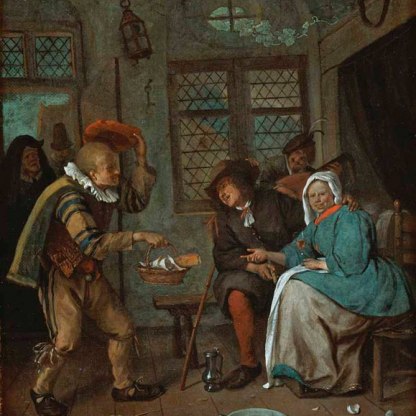

The hidden meanings behind some of the seemingly innocent objects in Jan Steen’s painting are relatively easy to decipher or guess at. The baguette-shaped bread that the man offers probably has phallic connotations. Similarly phallic is the recorder that the man seated next to the woman lets droop between his legs. Broken eggshells were suggestive of corruption and the loss of innocence – a quality that one imagines has been absent from this house for some time.

Other objects surrender their secrets less readily. Take, for example, the feathered cap worn by the rakish looking character sitting before the window. The fact of his being in a brothel allows us to guess the kind of man he is, and his distinct leer further defines him. In the seventeenth-century Netherlands, however, the feathered cap had direct sexual connotations. A 1614 poem by Roemer Visscher talks of men who 'triumphantly place Cupid’s feathered hat on their lecherous heads'.

The lute that he plays also has strong sexual overtones. The Flemish for 'lute' – luit – also meant vagina, and in Dutch art the instrument is often carried by prostitutes. The English writer Thomas Coryat recorded in his 1611 travel book, Coryat’s Crudities, that Venetian courtesans carried lutes as emblems of their profession. To find a young man playing upon one in a brothel with a broad smile upon his face should not therefore surprise us too much.

But the lute did not always necessarily imply profane love. Titian’s beautiful painting of Venus and the Lute Player in the Fitzwilliam [129], clearly deals with sex. But the music played there is expressive of a nobler type of courtly love.

And the song of the lute-playing angels in the fourteenth-century altarpiece by Niccola di Pietro Gerini, above [2078], is as far removed from the strumming of the young man in Jan Steen’s painting as heaven is from the whorehouse.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…