Waterloo

The outcome of the battle of Waterloo finally put an end to Napoleon's imperial ambitions. So crushing was it, that the word 'waterloo' has entered the English language to mean any ruinous defeat.

But as Wellington himself observed afterwards, it was 'a close-run thing'. Victory could very easily have gone the other way.

In 1814 Napoleon had abdicated, and gone into exile on the small Italian island of Elba. But on 1 March 1815 he re-entered France and descended on Paris with 1,200 men. Louis XVIII, who had been put onto the French throne by Napoleon's European opponents, fled to Brussels, and Bonaparte was once more declared emperor. He quickly set about raising an army of 124,000 men, determined to march on Brussels before his enemies – the British, Dutch, Prussians and Belgians – could muster an effective opposition.

Napoleon acted with speed, in order to be able to take on the Allies before they had a chance to unite. On 16 June, the French Field Marshal Michel Ney attacked the British and Dutch at Quatre-Bas while Napoleon himself engaged the Prussian army at Ligny.

The fighting was fierce in both locations. The British and Dutch were forced to retreat a few kilometres but managed to regroup at the village of Mont St Jean. The Prussians suffered considerably and Napoleon, believing that he had won a decisive victory, turned his attentions to the British. On the morning of 18 June, the French and British faced each other from opposing ridges, south of the village of Waterloo. Napoleon's troops significantly outnumbered those of Wellington. His artillery was superior.

But Napoleon had overestimated the amount of damage he had inflicted on the Prussian troops. Far from being routed, the Prussian leader, Field Marshal Blücher, now marched his remaining men to join Wellington and the Allies.

After heavy rain the night before, battle was joined at 11.30 a.m. The fighting was concentrated around three farms: Papellotte, Hougoumont, which the British managed to defend throughout the day, and La Haye Sainte, which the French briefly managed to overrun in the late afternoon.

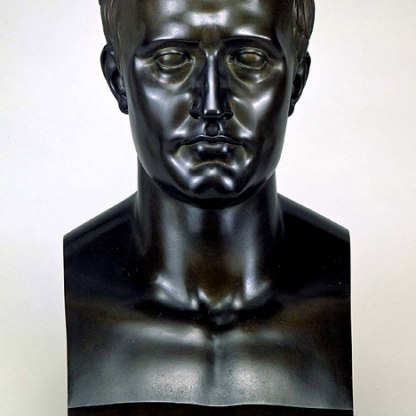

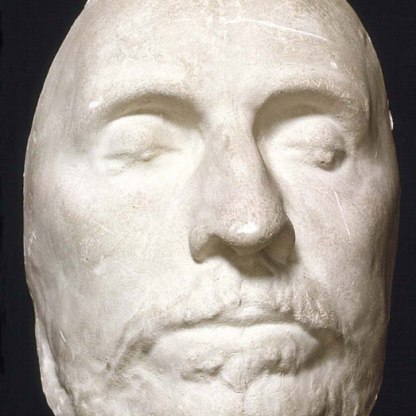

The battle could have gone either way throughout most of the day, but at around 4 p.m. Blücher’s Prussian troops arrived to attack the French flank. This tipped the balance in the Allies’ favour and, despite bold offensives, by the evening the French were on the retreat. Bonaparte himself had already fled back to France. He was forced to abdicate a second time on 22 June, and undertook a second, final exile to the island of St Helena in the south Atlantic, where he died in 1821.

Wellington by contrasts was now a national and European hero. He served as British prime minister from 1828 to 1830 with little success, but the reputation he won at Waterloo remained with him throughout his life. Rail travellers to Paris today on the Eurostar depart from the station named after his greatest, most close-run victory.

Other highlight objects you might like

Other pathways and stories you might like

Sign up to our emails

Be the first to hear about our news, exhibitions, events and more…